Introduction

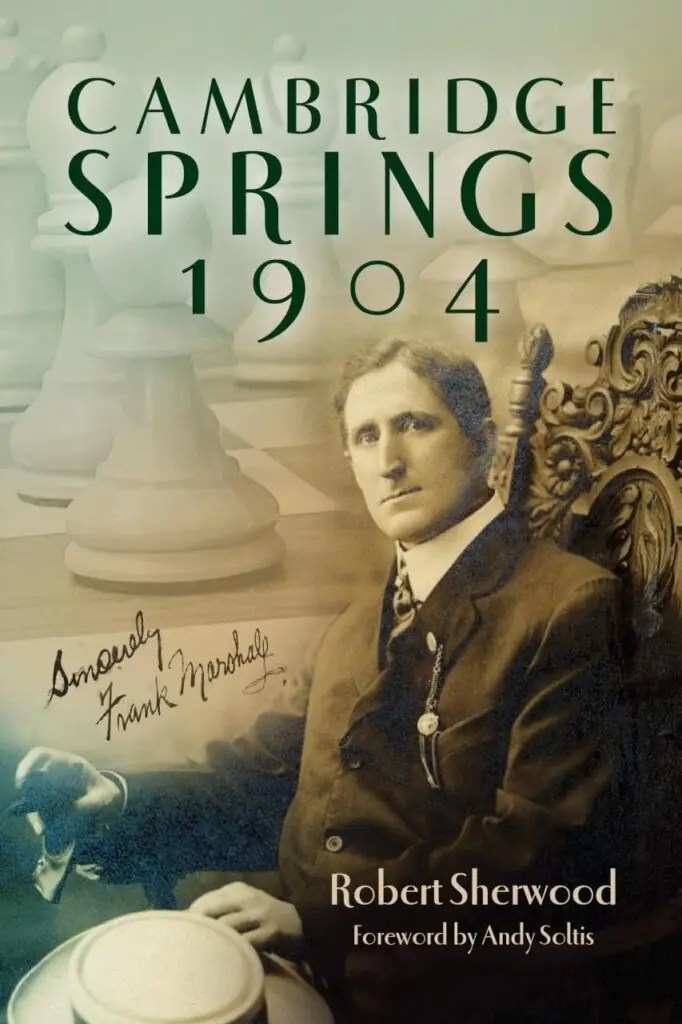

I was disappointed with the book. I seldom start my reviews this way, but I can’t begin the review of Cambridge Springs 1904 any other way. I’ll explain why in detail.

Cambridge Springs was a very important event for two reasons, both known to me before reading Sherwood’s book. Firstly, elite chess came to America for the first time since Morphy in the 1850s. In the break between Morphy’s European tour and 1904, the biggest success of American chess was Pillsbury’s performance at Hastings in 1895, which was remarkable. No event of international importance had taken place on American soil though. Even though Steinitz moved to America in 1883, and, after Cambridge Springs, Lasker in the 1890s, albeit briefly, there weren’t any strong tournaments that drew international elite players. There were attempts, but nothing of importance ever materialized. Cambridge Springs 1904 was thus the first major tournament in America, not just in the 20th century, but altogether.

This is the round 3 game in which Emanuel Lasker had white against William Napier, one of the lesser known players, who finished in 13th place. This is the position on move 14 for Lasker. How would you evaluate it? Is black’s position stable?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach! Try it out!

Secondly, despite being the underdog and a relatively unknown player at the time, Frank Marshall won the event without a single loss. His victory was unexpected. Lasker, the world champion, Janowski, Schlechter, Chigorin, and Pillsbury, were definitely considered stronger at the time. Perhaps Pillsbury unjustly so since he had already seen a decline in his health. He died just two years later, at the age of 34. Why is Marshall’s win important? Well, consider the importance of Fischer’s win in 72, Anand’s in 2000, or Gukesh’s last year. It was a turning point for American chess.

The book is a weird mix of the articles from the Bulletin that was coming out daily during the event, the first of its kind, and annotations taken from a variety of sources, many never quoted. Sherwood seems to have written very little himself. That, in itself, wouldn’t be a problem but for the way he organized the material and presented the games.

The Cambridge Springs Bulletin

Let me explain. The Cambridge Springs bulletin was the earliest example of an event publishing a daily recap of events. Sherwood used it as an introduction to each round. That’s by far the best part of the book. Many interesting pieces of information about not just the tournament, but the organization, and the players themselves can be found by a keen reader. It puts the games into perspective, gives them context and depth, and, frankly, without it, the book would be far less valuable.

What were Sherwood’s Sources?

Now for the biggest issue of Sherwood’s book – the lack of proper citations and him not mentioning where he took the annotations from. I read the book just like I always do, without paying much attention to the list of sources. After a couple of games, specifically in game 6, Lawrence-Janowsky, Sherwood gives Reinfeld’s notes after move 9: “This favorite variation of Chigorin’s was borrowed from him by Charousek and Janowsky, who also played it frequently.” (Sherwood 2022, 67) He simply put (Reinfeld) after the text. Now, I had never seen Charousek play the line in the game (I won’t list it here, but you can find the round 1 game online easily) and I wanted to see which game Reinfeld was referring to. So I looked for Sherwood’s sources. He listed Reinfeld’s The Book of the Cambridge Springs International Tournament 1904 published in 1935. So I could assume that the note came from that book. But, which page? How can you quote someone without proper citation?!

Two games later, in game 8, Barry-Napier, which was an interesting Petrov, Sherwood gives this note after move 9: “After forty-five minutes deliberation Barry concluded not to play into the fashionable variation 9.c3 f5 10.c4 Bh4. However, in the line chosen, Black’s ending is rather favorable.” (Sherwood 2022, 72) Sherwood put (Napier) after the annotation. Again, wanting to find out where Napier’s annotations came from, I went back to the sources. Nothing! I’ve no idea if Napier wrote a book or an article himself, if his annotations were included in the tournament bulletin, or if they came from Reinfeld’s tournament book, or one of the other 10 books listed as sources by Sherwood. What am I supposed to do with a quote without a proper source? Two other notes by Napier were included in the annotations to the game, again, without proper citation.

That made me incredibly frustrated. When reading chess books, my favorite part is getting lost in the sources and reading “around” the book. I usually grab all the sources, every book used while writing the one I’m reading, so that I can check the original text. Obviously, with Cambridge Springs 1904 I couldn’t do that.

What does Sherwood say? After finding out that I couldn’t get to the source of the citations he used, I went back and reread the intro. Sherwood says: “There was some existing journalism and analysis to work with. There was the Reinfeld book, published in the thirties, featuring notes and commentary by several of the players and by strong players from the generation after. The Wiener Schachzeitung offered a pair of articles and some analysis well worth including. The various game collections contributed interesting analyses and perspectives. All this would get added to my own analysis, corrected and deepened by the strongest contemporary software engines…” (Sherwood 2022, 5).

So we can safely deduce that when Sherwood is referring to “Reinfeld book, published in the thirties, featuring notes and commentary by several of the players and by strong players from the generation after”, he was taking notes from that book and quoting the players themselves, not Reinfeld. I tried to buy that book to get to the bottom of the issue, but I just couldn’t find it anywhere.

So, before continuing, I decided to try to get all of Sherwood’s sources. In total, he lists 11 books and the Deutsche Schachzeitung and the Wiener Schachzeitung, as well as Steven Etzel’s website on the tournament.

The books are:

Vabanque: Dawid Janowsky (1868-1927), 2005 by Daniel Ackermann,

Mikhail Chigorin: The Creative Genius, 2016 by Jimmy Adams,

Cambridge Springs 1904, 2019 by Michael Dombrowsky,

The Book of the New York International Tournament 1924, 1961 by Hermann Helms,

Napier: The Forgotten Chessmaster, 1997 by John Hilbert,

Das internationale Schachmeisterturnier in Karlsbad 1907, 1979 by Marco and Schlechter,

My Fifty Years of Chess, 1942 by Frank Marshall,

The Book of the Cambridge Springs International Tournament 1904, 1935 by Reinfeld,

Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion, 1994 by Soltis,

Why Lasker Matters, 2005 by Soltis, and

500 Master Games of Chess, 1975 by Tartakower.

How then, does he quote the following list of players and authors throughout the book: Reinfeld, Napier, Hoffer, Marco, Reti, Schlechter, Tarrasch, Fine, Marshall, Chigorin, Chernev? There may be others as well, I may have missed some. He also quotes “NFG”, and “NFC”. I don’t know what those are. The two magazines, the Deutsche Schachzeitung and the Wiener Schachzeitung are abbreviated as DSz and WSz.

Where did Fine’s annotations come from? Or Reti’s? Or Chernev’s? After continuing reading, I just stopped caring. Chess books shouldn’t be written this carelessly.

Sherwood’s Annotations

The book covers all the games. The tournament was a single round-robin played by 16 players – so 15 rounds total. That means 8 games per round, 120 games in total. The rounds and the games themselves are covered on pages 53-387. So 334 pages in total, for 120 games, which is just under 3 pages per game. Counting in the introductions from the bulletin, the notes by other players, that leaves us with very little room for Sherwood’s original annotations.

They aren’t detailed. What I like about them are the brief intros to each game, such as this one to game 4 played between Mieses and Marco: “A real Mieses game, replete with nineteenth-century risk-taking and bold play. Marco defends well until he rashly opens the position for his opponent’s bishops.” (Sherwood 2022, 61). Apart from the spoiler, which is given without warning in some of them, I liked the introductions. The annotations to the moves themselves are scarce. Many sidelines are given with text saying something like: “… is better but after …(moves)… black’s situation is grim. Also insufficient is (moves)…” That’s no way to explain an idea. That type of description occurs far too frequently for my taste.

He does give proper annotations in places, explaining the ideas, but not often. Some games are annotated in more detail than others as well, such as game 19, Lasker-Napier, a famous Sicilian. The inconsistency, and the lack of frequent detailed annotations, make the book very difficult to read, even with a board on the side.

Conclusion

This isn’t a well written game collection despite the enormous potential due to a vast amount of previous work done on the event, and the original tournament bulletin that came out in 1904. Sherwood’s annotations are not detailed, and the annotations by other players and authors aren’t quoted properly. I would advise you to read better tournament books.