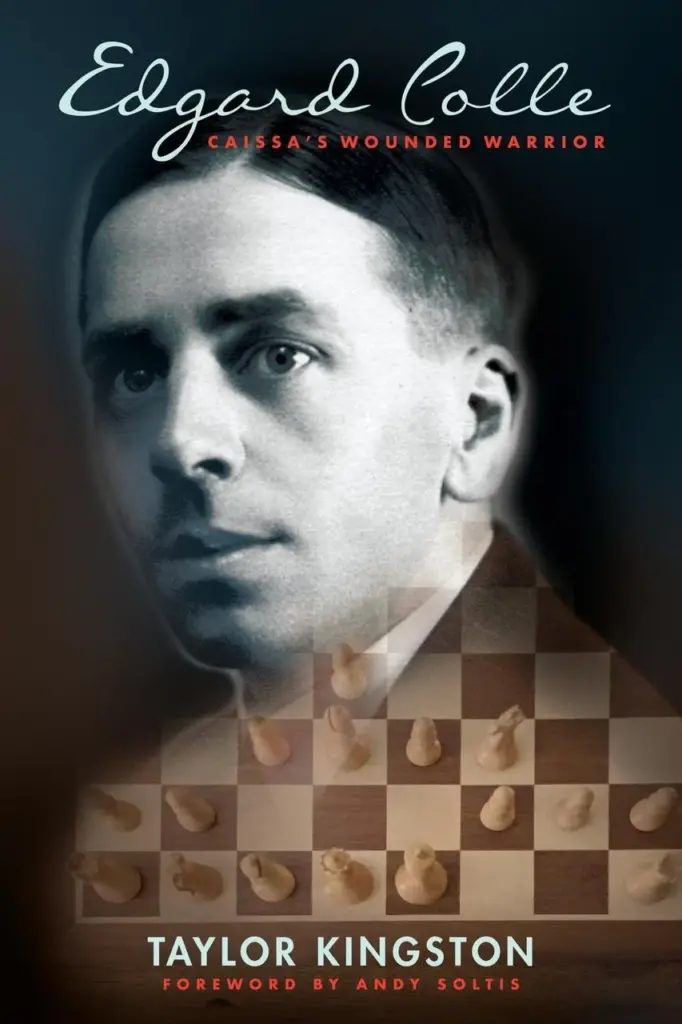

Introduction

Edgard Colle was a Belgian master. He died very young from a chronic case of a stomach ulcer that had been troubling him for the majority of his adult life. After many unsuccessful surgeries and attempts of recovery, he finally succumbed to the ailment in 1932, at the age of just 34.

His condition had a major effect on his life and his chess career. He would often visit physicians during tournaments, and seldom would a game or an event go by without it affecting his play. He was the 1920s Tal when it comes to health issues.

Despite this, by all accounts, Colle never complained, never blamed the illness for his poor performances, and highlighted his play as the reason for his defeats. More importantly, despite his illness, he managed to climb to the elite echelons of early 20th century chess, becoming one of the strongest players of his generation. And what a generation that was! His contemporaries were Capablanca, Nimzowitsch, Tartakower, Euwe, Alekhine, Maroczy, Marshall, Yates, Lasker, Janowski, and other geniuses every chess player has heard of.

Colle was by no means a prodigy, and his climb to the top happened in his 20s. His biggest successes came just 6 years before his premature departure. Much like Pillsbury, Stein, or, more recently, Vugar Gashimov, he was taken from the chess community during his prime, and we only wish we could know how high he could have climbed and what brilliancies he might have produced had he lived past 34.

Not much is known about Colle’s private life. Apart from his life-long friendship with Max Euwe, the, at the time, soon to become Dutch World Champion, and his book to tribute Colle’s life and games, Gedenkoek Colle, published in 1932, in which Euwe shared personal reminiscences and fifty annotated games, and Fred Reinfeld’s lesser known work titled Colle’s Chess Masterpieces, published in 1936, 4 years after Colle’s death, nothing of true significance has been written on the Belgian master.

The Colle System

Colle’s name is, of course, most often connected to the Colle system, an opening employed by Edgar often. He was one of the opponents of the classical chess approach that said that …d5 is the only response to 1.d4, and he challenged the 100-year-old rules set by the old masters that proclaimed that the QGD was the only sound way to play against d4 and that d4 c4 was the only sound response for white. When Nimzowitsch, Reti and Zukertort were introducing their 1.Nf3 hypermodern ideas, and Grünfeld was developing his modern defense to 1.d4, and the “Indian” defenses were first introduced, Colle came up with his own system – the Cole System. A seemingly unambitious opening setup that could be played without too much thought in which you play d4, Nf3, e3, Bd3, c3 and adapt from there depending on the setup black chooses.

He employed it regularly, and often produced stunning attacking miniatures. Today, and ever since Colle’s introduction of his system to the elite chess stage, it has been employed by almost every strong master at some point or another. It’s a sound deviation from the main lines similar to the London.

Many of the games, therefore, show Colle’s handling of the system, although the book isn’t a book on the Colle per se.

This is a position from one of the most historically significant games ever played, and not just by Colle. In Rotterdam in 1931, Colle and Rubinstein both played the final tournament game of their lives. This is it.

Structure of Edgard Colle, Caissa’s Wounded Warrior

The book isn’t structured chronologically, and Kingston doesn’t attempt to take us through stages of Colle’s career. Partly because of the lack of historical data due to Colle’s relative anonymity compared to heavily researched greats like Alekhine or Capablanca, and partly because the author wanted to show different nuances of Colle’s playing style in each chapter.

Other great biographical game collections you might like:

The book is divided into two parts. The first part covers previous overviews of Colle’s life and chess, and previous works on his career, including Kmoch’s article and eulogy in the Wiener Schackzeitung, the Gedenkenboek Colle written by Max Euwe, Colle’s Chess Masterpieces by Fred Reinfeld, and an article on his death from the Dutch publication Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad from 1932.

The second part of the book covers Colles games. 100 annotated games, and a few without annotations have been included. Kingston has divided the games into 11 chapters – Marvelous miniatures, An abundance of brilliancies, Colle lucks out, Follies, Failures, and Might-have-beens, Colle and the endgame, Colle and positional play, Colle’s fighting games, Salvaging the draw, Colle and Yates, Colle’s Gem, Swan song.

Each chapter is devoted to a particular type of games Colle produced; brilliant miniatures, salvaged draws, awful losses, positional masterpieces, or technical endgames. Personally, I love this type of division. The only drawback is not being able to follow Colle’s development though the years, but that is something the author has done despite the lack of chronological order.

Annotated Games

All together, Caissa’s Wounded Warrior consists of 110 annotated games. Reinfeld and Euwe, who had written works on Colle’s games in the 30s, have both compiled collections of 50 games, a great feat for that time considering the lack of media, and how hard it was to get reports from tournaments. This book does cover most of the games they have included, and even provides some of their original commentary, albeit with changes and modern analysis to back up their often mistaken assessments.

Every game has been analyzed by Stockfish and Komodo, probably the strongest engines in 2020, when the book came out. Most positions are given engine scores along with annotations. Taylor Kingston isn’t a master. Born in 1949, he was a strong correspondence chess player in the 80s, and he holds a USCF rating of 1811, so his analysis and notes must be taken with a huge grain of salt. Since he checked all the lines with engines, we can at least rest assured that there are no flaws in evaluations.

Kingston’s annotations are …ok. I guess. I was disappointed with them, but I almost always am. They aren’t as detailed as I would like, nor are they as descriptive and instructive as they could be. But they are still valuable. Kingston shares a bit of information on Fred Reinfeld in the first part of the book that seemed interesting to me. He talks about Reinfeld’s claim that he would annotate around 500 games per year for different publications. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never enjoyed a Reinfeld book. The annotation density is similar in Edgar Colle, and the quality slightly lower.

Many variations, especially sidelines are barren, with moves alone, and even large segments of the games themselves were left without any meaningful descriptions or explanations. That seems like unnecessary laziness on the author’s part.

Colle’s Tournament Successes

The author has done a remarkable job at listing Colle’s tournament performances. Colle was an aggressive, tactical player, who played rare systems and played for a win at all costs, which, at the time when the boring QDG equality was prevalent in elite chess, was a rarity. Colle, along with Spielmann and Tartakower, was considered a player who would produce interesting games and attract a crowd during tournaments. That is why he had been invited to over 50 tournaments during his last 10 years!

Kingston has listed his performances during those events. His successes were numerous, often scoring above greats like Capablanca, Rubinstein, Reti, or Tartakower. His biggest accomplishment, winning Merano 1926, fo example, is a remarkable feat.

For me, the most incredible part was reading the tournament standings and seeing players like Khan or Rubinstein there, and how Colle fared against them.

I have recently finished New York 1924, a wonderful book by Alekhine, and I wonder now, after reading on Edgar Colle, why he hadn’t taken part. Perhaps it was his illness that had prevented him from travelling. He had never played outside of Europe in his entire career.

Chess Stories from the Past

My favorite parts of the book are the episodes Kingston provides before annotated games and in the first part of the book.

One in particular, about a match Euwe and Colle had played in late 20s, struck me. They played an eight-game match. After seven games, the score was 4-3 for Euwe. Each of the first seven games had been won by white, and now, in the final game, Colle had to win. Euwe writes that they had been alone in the playing hall, and that they would often engage in conversations. During the final game, Colle mentioned how good his position was and that he was winning. Euwe challenged that claim and went on to win shortly after, and said that he should be more moderate when proclaiming his evaluations! Imagine that happening during a tournament game today! During their post-mortem, it turned out that Colle had been winning! Euwe writes how gentlemanly Colle was after the defeat, and how he said that Euwe had been right – that he should be objective and calmer. It takes a strong character to draw that conclusion after having lost a winning game. The two remained friends from that day to the day Colle died.

Many more episodes, including known players of the era appear in the book. They were thrilling to read.

Difficulty of Edgard Colle, Caissa’s Wounded Warrior

This is a game collection, and, by default, they are easier to go through than workbooks. But. This particular one doesn’t provide very detailed annotations which makes it very difficult to follow the games for lower rated players. That’s why I wouldn’t recommend this book to anyone below 1600 FIDE. It had taken me a long time to go through the games and set everything up on a board.

Conclusion

A wonderful overview of Edgard Colle’s life and career and not a perfect game collection because of the quality and quantity of annotations. Still, a remarkably enjoyable read and a book any chess enthusiast would enjoy.

Other game collections you might like: