Introduction

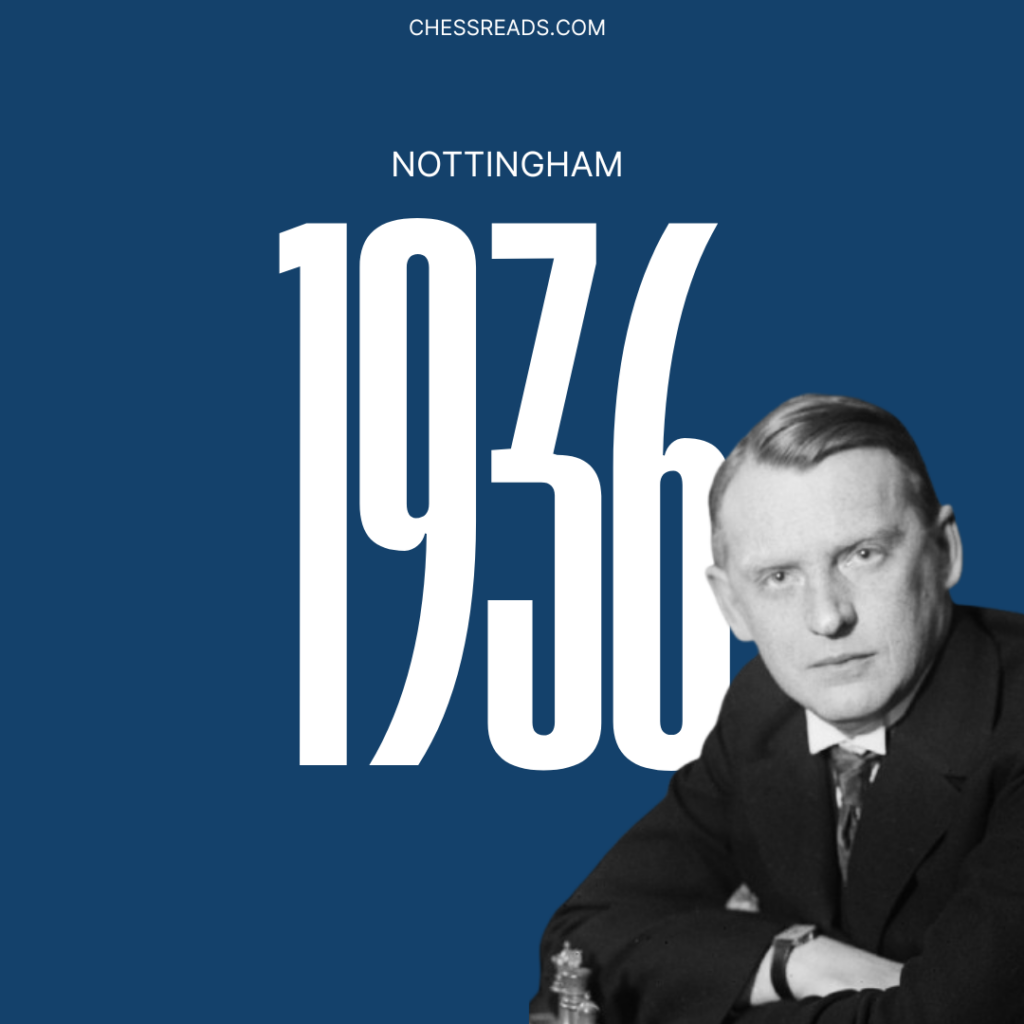

Nottingham 1936 was a remarkable event. Along with New York 1924, San Sebastian 1911, and AVRO 1938, it’s among the most important tournaments held before the modern chess era of Soviet dominance that began with Botvinnik winning the 1948 World Championship tournament in Hague.

It set a record for having four world champions; Capablanca (1921-1927), Alekhine (1927-1935, and later 1937-1946), Euwe (current world champion, 1935-1937), and Lasker (1894-1921). This record was broken in 1964 when four Soviet champions started appearing at tournaments together frequently. Botvinnik, who was to join them as the next champion, played as well.

The four champions were joined by young talents, up and coming players who were expected to do well, perhaps even outperform the top guys; Fine, Reshevsky, Flohr, and the young Mikhail Botvinnik, who was only 25 at the time.

Other participants weren’t serious contenders for the title, either because of their age, or playing strength. Tartakower, Vidmar and Bogoljubov were past their prime, despite being world class. The rest of the field was composed of four invited British players, Tylor, Alexander, Thomas and Winter. They had, expectedly, finished in the last four spots.

Interestingly, the final standings weren’t surprising at all. The young guys and the champions finished 1-8, the three veterans, Vidmar, Tartakower and Bogoljubov 9-11, and the British invitees 12-15.

Reuben Fine faced the great Lasker in round 1. Lasker had black and move 18 he played Ndf6. Alekhine writes: “It is really hard to understand why Dr. Lasker rejected the natural 18…Nf4. The only plausible explanation is that he did not like after 19.Qe3 Nxd3 the possibility of 20.Rc7 (20…Rac8 with equality) and answering the move 20…Bc6. If 21.Rxc6 (or 21.Nb6 Nxb4; etc.) Nd7e5 22.Nxe5 Nxe5 23.Rc5 Rfd8 etc., he would emerge from the difficulties.” How would you evaluate the position after Lasker’s move?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach! Try it out!

The Four World Champions

Lasker was definitely past his prime. Despite that, he played well and finished in 8th place. Alekhine had lost the title to the young Max Euwe a year before Nottingham. Euwe won because of Alekhine’s lack of discipline, or so most historians say. In any case, Alekhine was surely the stronger of the two, proven by the rematch in which he regained the title in 1937, making Euwe’s reign short and relatively unimpactful.

Alekhine was probably past his prime. Most books and sources talk about his decline after the 1927 match. His lack of work and preparation, similar to that of Capablanca, marked the end of chess talents who would climb to the very top without tremendous effort. British reporters mentioned that Alekhine was chain-smoking throughout the entire tournament and that he had smoked over 100 cigarettes during a single game! Soltis says that “…Alekhine set the nervous tone to the tournament.”

Capablanca, who was definitely nearing the end of his career (he died in 1942), staged a marvelous comeback in 1936 and played a tournament way above his performances since 1927.

Botvinnik, the Future Champion

Botvinnik and Capablanca shared 1st place with 10/15. Botvinnik, 25 at the time, had a new approach to elite chess. His methods are still applied today. Hard work, extensive preparation, detailed analysis, is what made him the best. Unlike the older champions, he was the first to combine talent with truly hard work and complete devotion to chess.

His games from Nottingham show that he was already a well-rounded player in 1936. Had it not been for the second world war, and the trouble with arranging a match with Alekhine, and, finally, Alekhine’s mysterious death once the match was finally arranged, I don’t doubt he would have taken the crown sooner than 1948.

Alekhine’s Analysis and Annotations

This is Alekhine’s last tournament book, after New York 1924 and New York 1927. Soltis mentions in the introduction that Alekhine’s annotations are still Pre-Soviet. Soviet era books are, according to him, antiseptic, and have an anonymous tone of annotations. That is definitely true with Nottingham 1936 and with Alekhine’s other books. His notes are quite personal, subjective, salty, and sometimes even insulting. To be fair, though, he treats himself the same as all other players. He writes about himself in the third person, which is slightly odd. He does that in all his other books too.

Soltis says that the book was written “by a more mature, self-confident Alekhine. Earlier in his career he embellished if not outright lied about some of the moves he played and how much he had calculated.” I’m not good enough to notice that! I have read most of Alekhine’s earlier books and I haven’t felt that he was exaggerating or embellishing the annotations. Andy Soltis is both a great player and an author and chess historian, so I will take his judgement as the truth.

Alekhine has annotated all 105 games played during the 15 rounds. In each round one player had a bye. His annotations were unchanged in this new Russell edition from 2024.

They are, to an experienced reader, already recognizably Alekhine’s. He writes well, and he doesn’t try to cater to an uneducated chess audience. His notes are on a high level and meant for players who’ve gone way past the basics. He often fails to explain simple tactics, or consequences of obvious mistakes, which is natural. Thus, beginner players will have to do a lot of work on their own to make sure they follow the games.

The annotations could (as always) be more detailed and denser. Annotating 105 games in less than 180 pages should tell you a lot about the level of detail. Less than two pages were devoted to each game. Ideally, each move would be annotated, but that was never the case in the old days. For comparison, Tal has written around the same number of pages while covering 21 games played during the 1960 Tal-Botvinnik match.

Other Books by Alekhine or on Alekhine You Should Read

The Games from Nottingham 1936

The games are remarkable. The Dutch played often, many fighting draws, and only a few “agreed” ones, notably Capablanca’s round 1 19-move bore against Tartakower. Apparently he was running late and had missed lunch so he wasn’t up for a fight.

Alekhine mentions that this is the first tournament during which the 30-move rule didn’t apply. Meaning that one could draw without having to reach move 30. He writes: “For the first time, in England at any rate, the FIDE rule that no game shall be agreed drawn in less than 30 moves is done away with, since the rule is so easily evaded when desired.”

The time control was changed in Nottingham. It was 36 moves in two hours. By today’s standards, that’s a great deal compared to our usual 90+30, but at the time it was like rapid. Botvinnik said “I was young then and managed quite well” even though it was the fastest time control he ever played.

Nottingham 1936 was a tournament of many “firsts”. The young Botvinnik played Alekhine, Reshevsky, Fine, Vidmar and Bogoljubov for the first time. Reshevsky played Lasker, Flohr, Euwe, Tartakower, Vidmar and Bogoljubov for the first time. Alekhine and Capablanca played their first game since their match in 1927!

Conclusion

Nottingham 1936 is a short game collection that covers every game played during the important tournament. Alekhine has annotated every game himself. His annotations are standardly good but not as detailed as they could be. Any advanced player would have an easy time following the analysis with a board on the side. Without one, following all the variations would be almost impossible for anyone below FM level. A good game collection about a very significant event that saw 5 world champions compete!

Other Game Collections You Might Like

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- First Grandmaster of the Soviet Union: A Chess Biography of Boris Verlinsky

- Sergei Tkachenko

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- The Wizard of Warsaw: A Chess Biography of Szymon Winawer

- Tomasz Lissowski, Grigory Bogdanovich