Introduction

I have to begin the review of The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein with a brief disclaimer. Gennadi Sosonko, the author of the book, is a Soviet-born Dutch grandmaster and a prolific chess author. He has written numerous biographical and historical chess books that depict the life and chess during Soviet times, a period spanning from the 40s to the early 90s during which the Soviet chess machine managed to produce five consecutive world champions – Botvinnik, Smyslov, Tal, Petrosian, and Spassky, and, after a brief interruption by Bobby Fischer, two more, Karpov and Kasparov.

Sosonko’s books on the era include Evil-Doer: Half a Century with Viktor Korchnoi, The World Champions I Knew, The Reliable Past, Smart Chip from St.Petersburg, Russian Silhouettes, Genna Remembers, and The Essential Sosonko, a collection of his portraits and stories written over the span of his career.

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein, published in 2017 is the first Sosonko chess history I’ve read. Reading it was an eye-opening experience, and I learned more about how Soviet chess worked than in 9 years of reading various other chess books and resources. The disclaimer is – I don’t think I will be able to do Sosonko and the book justice considering that, in order to do that, I think I would have to read all his other works first. I think, therefore, that my understanding of The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein, Genna Sosonko, and that of the Soviet chess era as a whole, would be significantly better, and complete after reading the rest of his works.

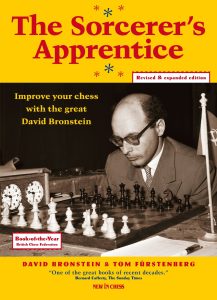

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein is a short book, 270 pages long, that covers the life of David Bronstein, a man whom many consider one of the strongest players of the 20th century never to become world champion, along with Rubinstein and Keres.

Sosonko knew Bronstein. They talked often, they played each other, and they have many shared acquaintances. Most importantly, they were a product of the same regime, during which chess was organized and played a certain way – the way the authorities proclaimed it should be played.

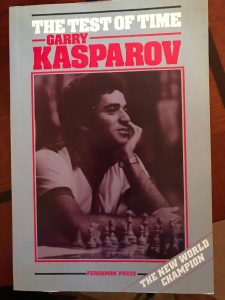

Soviet era grandmasters can often be divided into those who supported the regime and those who opposed it – that distinction often further fueled rivalries, taking them beyond the chess board. Bronstein was an individualist, his nemesis, Botvinnik, a regime poster boy. The same can be said of Kasparov and Karpov, Kasparov, a young rebel, a dissident, and Karpov, who, much like Botvinnik before him, was a picture-perfect example of Soviet excellence and obedience during his peak.

Sosonko brings forward Bronstein’s thoughts, feelings, statements, problems, successes, and failures, through the medium of the conversations they had been having over the long years, and through what seems, at least to me, an uneducated reader, original research.

David Bronstein was …Special

One thing is obvious – Bronstein was a special man. He was an individualist, an eccentric, a chess pioneer, and an attention seeker with complex psychological issues. Furthermore, he enjoyed his status as an oddball, someone whose answers, world views, and even chess games must be, by default, unique, interesting, and groundbreaking. Sosonko explores Bronstein’s troubled mind through the prism of his chess career, which, understandably, cannot be disconnected from Bronstein the man. Chess players, for good or bad, are equated with their successes over the board.

Bronstein was, or, at least during the latter stages of his life, became a cynical, pessimistic, unpleasant man. “Let me tell you something: I don’t like any of my books. The one they all praise, the Zurich book, it’s stupid. I didn’t actually write it, after all.” This, and many other excerpts from the conversations he had with the author depict his state of mind. “The thing is, I didn’t actually want to defeat Botvinnik. I wasn’t playing for glory, I have no interest in glory, in fact, I was simply trying to please the crowd.”

Books written by David Bronstein:

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- The world Chess Crown Challenge: Kasparov vs Karpov, Seville 87

- David Bronstein

“Chess isn’t worth being written about the way you write about it. It’s not worth it.”

“You and I are in a similar hole, except that this hole is called chess. And I’m sorry that we were dragged into this hole and that I couldn’t climb out of it. I was interested in life, not just chess, and I overestimated my strength.” These, and many other tidbits of conversations taken from the last 20 or so years of Bronstein’s life show a strange character, troubled by regret. I can’t help comparing him to Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm or George Costanza in Seinfeld (two almost identical characters). They, albeit comically and in a fictional setting, often produced the same type of completely uncalled for cynicism and pessimism.

Bronstein’s Chess Career

Sosonko begins by covering Bronstein’s early years and his ascent to the chess elite, which was, to put it mildly, remarkable. The book can be divided into two parts – pre match with Botvinnik, and after the match.

In 1951, Bronstein played the great Mikhail Botvinnik for the crown. This was the greatest, most influential episode of his life. It influenced his thoughts and penetrated his psyche, troubling him for the rest of his life. He failed. The match ended 12-12, despite Bronstein being up a full point with 2 games to go. I won’t focus on the chess itself here, even though the match was remarkable, featuring many Dutch Defenses by both players, and many great attacking games. Bronstein played well, but not well enough to dethrone the king.

Botvinnik, who had become the world champion in 1948, by winning a quadruple round robin which was to determine the new champion after the mysterious death of Alexander Alekhine, was the perfect champion. He was calm, composed, known for his hard work – a perfect Soviet poster boy. Bronstein, a young, scrawny, weird, thin boy from the provinces, who played attacking chess and had bad endgame technique and no college degree was surely unfit to replace him. In a way, Bronstein attempted in ‘51 what Tal succeeded at in 1960. Tal was very similar to Bronstein, both in their chess style, and their inability to conform to Soviet norms.

Soviet Chess, Match-Fixing, and Bronstein’s Dishonourable Ascent

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein has several main characters along with Bronstein himself; Boris Vainshtein, the key figure in David’s life, was a party member and his patron. He was responsible for Bronstein’s ascent as much as the man himself. He supported him financially, logistically, and vouched for him within the system, something without which Bronstein would never have been able to succeed, or even travel to tournaments abroad.

Vainshtein was 17 years David’s senior. He became a true father figure, acting as his second, arranging matches and games, providing support. Bronstein even lived in his Moscow apartment for several years. Zurich 53, Bronstein’s most famous book was even, as Bronstein admitted himself, written by him: “The truth is that Vainshtein wrote it. I only provided the variations and the analysis.”

The second side-character is Isaak Boleslavsky. David’s childhood friend, and his companion throughout his entire career, was a supporting, loving figure, less ambitious than Bronstein, but equally strong a grandmaster. The most important episode I must mention here is their match that preceded the 1951 world championship. During the candidates tournament that was played to determine Botvinnik’s challenger, Vainshtein, the omnipresent, powerful figure in David’s life, had managed to arrange the games in a way that had given Bronstein the chance to play Isaak for a chance at the title in a match. Without his nudging, and without him proposing that Boleslavsky draws unnecessarily in the final rounds, Boleslavsky would have been the sole winner and the match would never have taken place.

But it did. And both Boleslavsky and Bronstein agreed to Vainshtein’s dirty proposal. Their match is an even bigger disgrace. It had been predetermined! Bronstein was to win the match, and both players knew it. They didn’t fight, they didn’t even play real games. The final game, in which Bronstein “won” convincingly with black was composed beforehand. I was astonished to learn this.

Bronstein said later on in his life that he had not only failed to defeat Botvinnik, but he had also brought dishonor to his name and legacy – supposedly referring to the way he got to play the match. It seems like Fischer was right when he called the Soviet chess players out for cheating.

The Match Against Botvinnik

People rooted for Fischer against Spassky, for Tal against Botvinnik, for Kasparov against Karpov, for Carlsen against Anand, and for Bronstein against Botvinnik. It’s human nature to support the new, up-and-coming, young, exciting, different, and unconventional players.

This is a position from a King’s Gambit game played by Bronstein. It’s black to play. How would you evaluate it?

On Chessmind you can solve positional problems and get instant feedback like you would from a real coach, you can learn from numerous opening courses, practice tactics adapted to your strength, and get access to ChessGPT! Try it out!

Thus, in Moscow in 1951, the match began. Botvinnik, who had been idle for 3 years, and had barely played chess since his 1948 match, and Bronstein, who had, despite his arranged games and a somewhat dishonorable ascent to the top, played a lot and was in much better form.

Botvinnik won the match. That’s all there is to be said about it. And I’m glad he did. I don’t think Bronstein deserved the title. He was a great player, there is no doubt about that. He was also a great innovator, whose ideas can be seen in modern chess today. He was weak in two important areas though – chess psychology and technique. He wasn’t even close to Botvinnik in technical positions and he was unstable, unable to deal with the pressure of a match.

After the match, until the end of his life, the defeat haunted him. If The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein is about one thing, it’s about David’s inability to cope with the match and with the fact that he came half a point away from achieving his dreams. He claimed later in life that he didn’t really want to win, that he wasn’t good enough to win, that he didn’t care that he lost, that Botvinnik was better anyway and that he was just a stupid boy with delusions of grandeur. I can’t help but agree with some of his statements, but he is being dishonest to his former self. Before, during, and after the match that was all he cared about, just like anyone else would. And the defeat broke him. He never recovered.

In a way, The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein is a sad book. I read it to Lucija out loud. She normally doesn’t read chess books with me, since she doesn’t play, but I tend to tell her when I’m reading histories and biographies. Even she was captivated by this book. I think everyone, regardless of whether they play chess or not, would enjoy it.

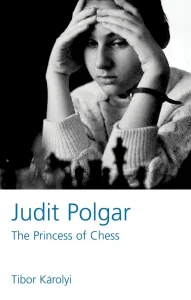

Other chess biographies you might like:

- ELO: 1800

- -

- 2000

- Unveiling the Victory, How Spassky Won The Third World Junior Chess Championship Antwerp 1955

- Henri Serruys