Introduction

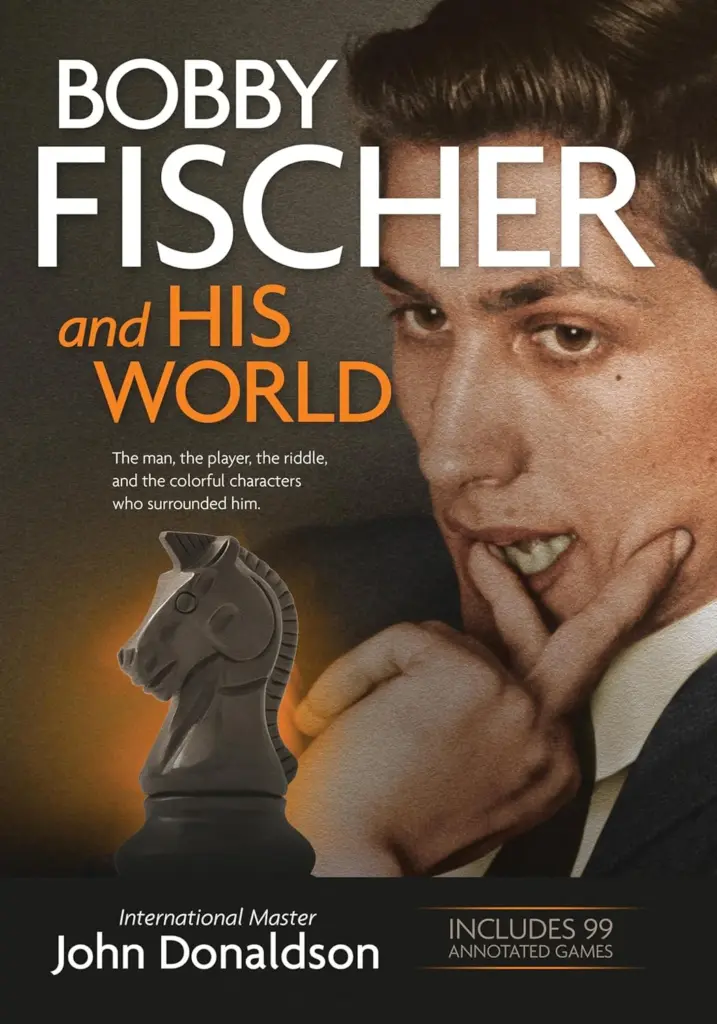

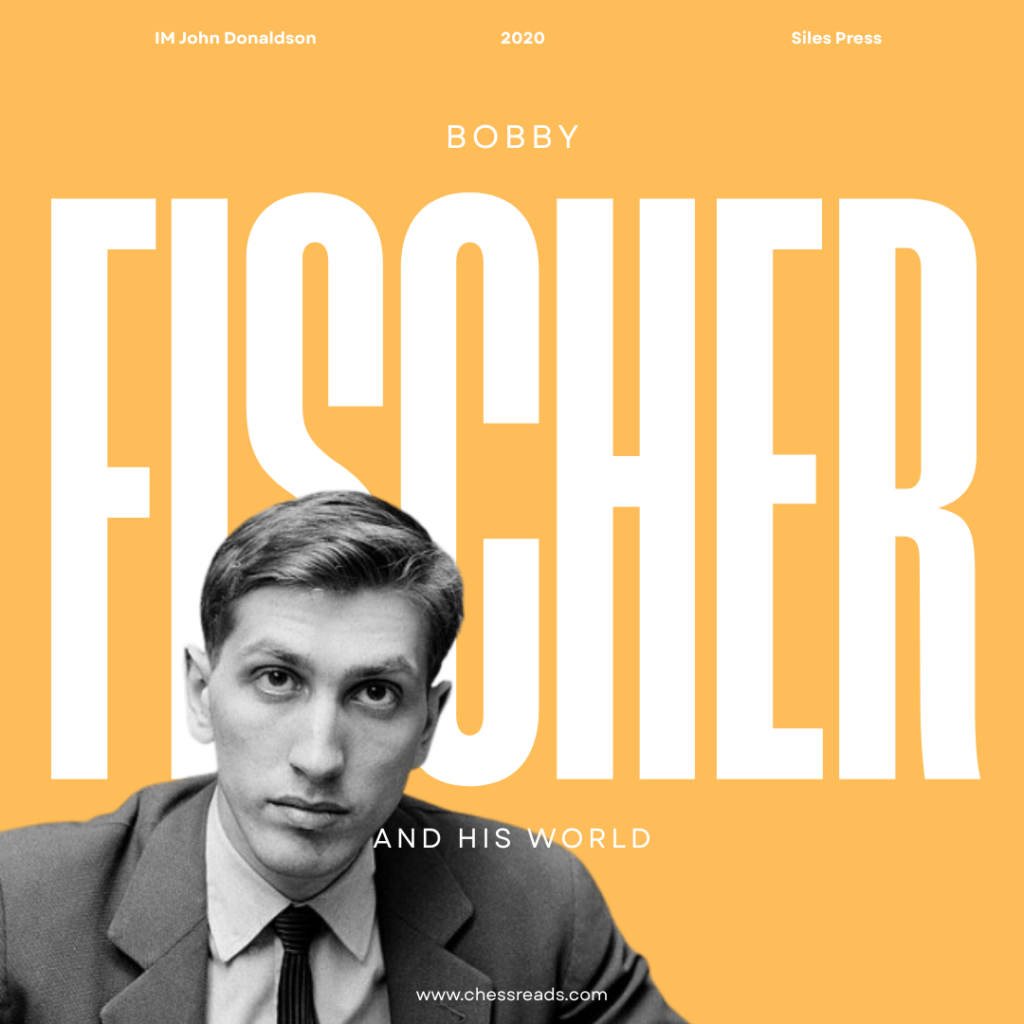

I don’t know if your country has seen the same unstoppable wave of fancy bakeries that we’ve had in Croatia. There are only two bakery chains now and they are replacing hundreds of small bakeries and shops all over the country. They are better than the old ones, with uniform products, like a fast food chain. John Donaldson is doing that to every other book written about Bobby Fischer. Bobby Fischer and His World is more detailed than the majority of other sources on Fischer combined. Because of it, there seems to be almost no need for the other books.

The reference to bakery chains may sound negative, but it’s the opposite. Having access to one book on Fischer that explains everything is wonderful! Having read Donaldson’s Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer just last week, I can safely say those two books are the definite source on my favorite chess player and I doubt that will change unless groundbreaking new information is discovered. Simply put, Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer covers everything Fischer ever wrote, and Bobby Fischer and His World tells his entire life story, along with the stories of every person who influenced his chess, personal life, or decision making.

The Ultimate Book on Fischer

I liked to think that I knew a lot about Fischer. After reading Bobby Fischer and His World and Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer I realised that I knew close to nothing. Donaldson has covered Bobby’s early life, as well as his life after the 1972 match with Spassky in greater detail than anyone ever before. Donaldson references every available source on every stage of Fischer’s life, including numerous discoveries that have been made since what were considered Fischer bibles, such as Frank Brady’s Endgame, or Euwe and Timman’s Fischer World Champion. Simply put, I don’t think anyone has come close to the level of detail provided in this single, 600-page volume.

I read it in two days. I couldn’t put it down. So many questions I wanted answers to were answered. I was given context for many tidbits of information I knew about Fischer’s life and chess, and, page after page, I kept discovering the true meaning behind many of Fischer’s controversial decisions.

Being a Fischer fan, I was mostly interested in his early years and his post-72 life. Donaldson doesn’t disappoint. Bobby’s development and meteoric rise from a 1700 to a 2600 player within just a couple of years finally made sense to me. Every single one of his tournaments and games available is used to explain his meteoric rise. Donaldson gives detailed accounts of his peers, other strong juniors at the time, his “coaches”, people whom Fischer worked, trained or spent time with, shedding light on what contributed to his development from a regular kid, who was by no means a prodigy, to the best player in the world. The book includes sources and Donaldson’s own text in equal proportion.

By profession, I’m a medieval archaeologist. I spent my college years reading history and archaeology. Those books are often, considering they deal with events that took place a millennia ago, collections of available information with as little guess work as possible. They reference sources and try not to provide hypotheses or conjectures, but a summary of reliable facts on a topic. Bobby Fischer and His World is the only chess biography, along with, perhaps, Jakobetz’ Chess Warrior, The Life & Games of Géza Maróczy, that feels like actual scientific work.

What struck me the most is that Donaldson has never shared his own opinion. At over 600 pages, the book covers (I think, my knowledge of Fischer was obviously lacking before reading it) everything we know about Fischer’s life. The information is presented without bias, even when it comes to very controversial topics, such as Fischer’s involvement in the Worldwide Church of God, his not defending the title in 75, or his 1992 return match with Spassky. Knowing how to write without imposing your own opinions and without embellishment or conjecture is a rare feat. It made me trust everything Donaldson wrote as fact.

Bobby Fischer’s Four Chess Books

In Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer, his new book on Fischer, IM Donaldson dissects Fischer’s writing. He covers all four books Fischer wrote, as well as his numerous articles in chess columns.

- ELO: 1400

- -

- 1600

- Chess Meets of the Century

- Bobby Fischer, Dimitrije Bjelica

Fischer’s Unknown Games

Donaldson had access to information never published before. Among others, he used the libraries and collections of the DeLucia family, the materials collected and stored by Fischer’s brother-in-law – the Targ Collection, and the largest collection of Fischer memorabilia held by the Sinquefield family in the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discoveries were made from the Targ Collection, after Russell Targ, Bobby’s brother-in-law. In 2008, after Bobby’s death, he donated the collection to the Marshall Chess Club. Donaldson was invited to view the collection in 2013. He writes that “Much of the material was family related (not dealing directly with Bobby’s chess career) and provided great background material: Frank Brady had access to it when he wrote Endgame.

Joseph Ponterotto relied heavily on it as a primary source for A Psychobiography of Bobby Fischer. However, the real gold was hidden under the family papers – Bobby’s score sheets from his youth. I would guess there might be anywhere from seventy-five to one hundred score sheets (some signed and some not) dating from 1955 to around 1960” (Donaldson 2020, 47-48). He goes on to say that the collection included a number of games thought to be lost forever. He wasn’t allowed to record games, which I cannot understand. He made a list of games from memory a few hours after viewing the collection.

Donaldson gives a list of all unknown games he found (pages 48-49). Some of them have since been made public, but most remain a mystery. Many of them were played at clubs Fischer frequented, and included training games and games from thematic tournaments, such as the Ruy Lopez tournament held in 1957.

Donaldson rightly mentions how Fischer memorabilia and especially unpublished games have a high monetary value. I hope the club sells them one day.

This is a position from a rarely quoted Fischer game I really like. It was played at the 1957 US Open held in Cleveland. Young Fischer, who was only 14 at the time, had the white pieces against William Addison. They played a Two Knights Attack in the Caro-Kann. Fischer chose a rare line for 1957! Later in his career, he almost always played the Exchange Variation against the Caro-Kann. It was Bobby’s turn on move 21 in this complex endgame. Who is better and why? How would you evaluate this typical Caro-Kann structure?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach! Try it out!

Examining Fischer’s Peculiar Mind

Most uneducated readers (myself included) know Fischer won the 72 World Championship against Spassky, and that he went crazy after that. Reducing him to that is not only unjust, but plain wrong. Donaldson gives detailed accounts of everything that went on in Bobby’s mind from when he began playing tournament chess, to his final years in the early 2000s in Iceland. He does so without prejudice, without condemning Fischer (which is refreshing), and by providing real accounts, letters, conversations, and interviews that shed light on why he behaved the way he did.

Many of the resources quoted and shared in full struck me as “key” for understanding Fischer. One in particular, which I’d like to mention, is the period after the 72 match and before his 75 forfeit. Having become the champion, Fischer didn’t, as is commonly thought, try to avoid the Karpov match. He tried to improve playing conditions for all players. He never backed down if he thought his requests were just, proven by an episode given by Donaldson that happened when Bobby was just 18, way before his “crazy years”, when he dropped out of a match because a game was due to be played in the morning (he was a late riser).

In any case, after his win over Spassky, Fischer fought a war with the organizers to have his conditions met. Donaldson gives his letter to the FIDE officials in full (Donaldson 2020 481-483). Reading it made me realise that he was perfectly sane, and absolutely correct! He proposed several changes that sound more than reasonable, such as not allowing committees to select some of the participants of Interzonals, expulsion of any country from FIDE on a political basis, a limitation of prize funds, or the shortening of world championship cycles. He also gave detailed opinions on formats of matches. It seems to me, that had they accepted his proposals, the chess world would have only benefited.

Many other episodes from Fischer’s life are covered in detail. Most notably, his involvement with the Church of God in the 60s, his giving them a hefty portion of his 72 match winnings (over $60 000), and his subsequent withdrawal from the organization. His conversations with an interviewer in the mid 70s shows that he was aware of how controlling the organization was, and how he knew exactly what he was doing when he was trying to support them financially. He mentioned that the most important thing, and why he’s speaking out, is that they don’t “rip off anyone else mentally”. His entire interview, or recording of his conversation with Len Zola, and the subsequent lawsuit Fischer started because he claimed they weren’t allowed to publish it, is given, along with (Donaldson 2020, 489-493).

I could mention twenty other episodes which struck me as key in Fischer’s shift from chess player to a sort of anti-establishment, anti-propaganda paladin, whose main purpose in life became hiding information about himself and combating anyone who spoke of him, whether for good or ill, to the press.

Other Books on Bobby Fischer

99 Annotated Games

The book covers 99 annotated games, not just by Fischer, but other relevant games too. The notes were sometimes by Fischer or other players, and sometimes, I guess, since it’s not always specified, by the author himself. Some of them have never been published before, and some, especially from his early career, were unknown to me despite being public for years. The book includes unofficial games as well, such as his training match against Gligorić in 1992 in prep for Spassky. I loved those. Not the games themselves, but the stories behind them. I wouldn’t say this is a chess book or a game collection. It’s a book on Fischer, and not having chess in it wouldn’t make sense. But don’t think of it as a learning resource first.

Conclusion

Bobby Fischer and his World is the ultimate book on Bobby Fischer. Never before has anyone collected so much information, both already known and previously unpublished on a chess player. Donaldson covers Fischer’s life from his early teens, when he was just an ordinary kid, not a chess prodigy, to his late years while he lived as a recluse in Iceland. Being a Fischer fan, this was an eye-opener for me. I learned that I knew nothing about Fischer before reading the book despite having read almost everything published on him previously. This book makes all other Fischer biographies obsolete. Read it.

Other Chess Biographies You Might Like

- ELO: 1800

- -

- 2000

- The Life and Games of Vasily Smyslov, Volume 1: The Early Years 1921-1948

- Andrey Terekhov

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- The Wizard of Warsaw: A Chess Biography of Szymon Winawer

- Tomasz Lissowski, Grigory Bogdanovich

- ELO: 1800

- -

- 2000

- Chess Warrior, The Life & Games of Géza Maróczy

- László Jakobetz

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- Alekhine’s Odessa Secrets: Chess, War and Revolution

- Sergei Tkachenko