Introduction

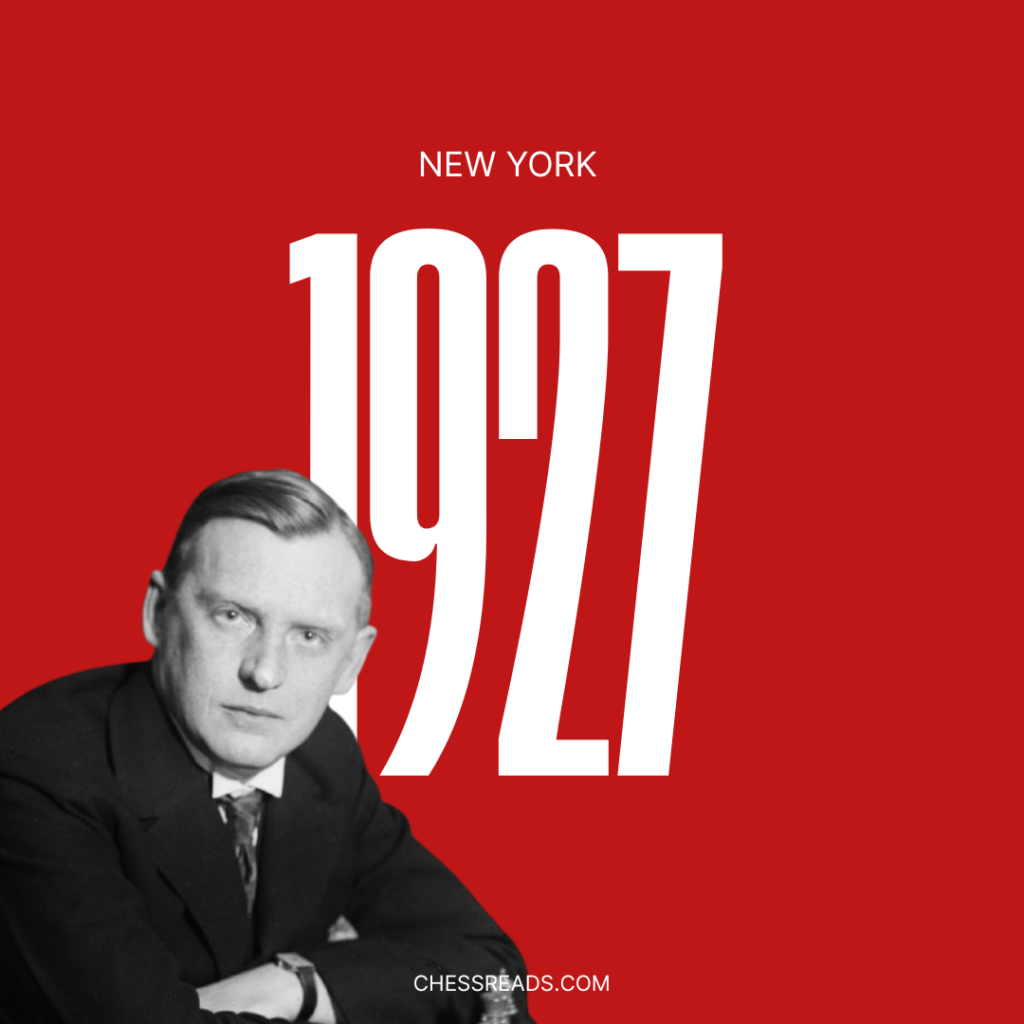

New York 1927 is Alekhine’s most fun and least professional book. And by a very large margin. I don’t mean that judging by his annotations, which are as instructive in New York 1927 as in his other books, but the fact that the entire thing seems to have been devoted to unveiling how Capablanca was, in his opinion, a flawed player, and not the “chess machine” people have been mistakenly taking him for. His coverings of New York 1924 and Nottingham 1936 were professionally written books. They were meant to teach chess and, more importantly, present the games from the tournament objectively.

The book came out in 2011. The original book was published in German in 1928, with a Russian edition from 1930. This is the first English edition.

Alekhine vs Capablanca, the Biggest Rivalry in Chess

It’s important to put New York 1927 into perspective. The event took place in early 1927 in New York, about six months before the match in which Alekhine overthrew Capablanca as the world champion. Based on the (abridged it seems) version of the entire story given by Alekhine in the introduction to the book titled “The 1927 New York Tournament, as Prologue to the World Championship in Buenos Aires”, and based on the players’ performances in previous events held in the 20s (Moscow 1925, New York 1924, and others) we can conclude several of his statements to be factually true.

Firstly, Capablanca was by no means an easy champion to arrange a match with. According to Alekhine, his attempts at arranging a match in 1921 and 1923 failed. Secondly, Alekhine was a worthy opponent. Along with Bogoljubov, Nimzowitsch, and Rubinstein, he stood out among the chess elite of the 20s.

Thirdly, regarding the match invitation(s), Alekhine writes: “In the autumn of 1926, the then-champion (the book came out after their match) received two challenges to a competition for the championship – one came from Aron Nimzowitsch, the other from me. It soon became apparent, however, that Nimzowitsch’s attempt was of a “platonic” nature, since he lacked a small thing, namely the financial support to fulfill the conditions coming out of London.” He must be referring to Capablanca’s match demands. He continues to say “…The case was different with the telegram I sent Capablanca in September from Buenos Aires… I was determined to send a challenge only if I would have an absolute guarantee on the part of the interested organizations that, financially, nothing would stand in the way of the realization of the match.”

Alekhine then writes that he’d assumed that nothing could stand in the way of Capa accepting the challenge. Things turned out differently. Capablanca neither accepted nor rejected the request. For more on this and other episodes that showcase their life-long rivalry I would advise you to read Siles’ Capablanca & Alekhine, a book devoted purely to their relationship. In short, Alekhine got a letter from Capablanca saying that he should come to New York 1927 and that the tournament would decide the challenger for the World Champion. He says that that put tremendous pressure on him, partly justifying his poor performance in the event. Was it Tartakower that said “I have never faced a healthy opponent.” Alekhine writes: “Partly because of this psychological handicap, I had very serious concerns before I accepted the invitation. Finally I decided (to go) mainly for the two following reasons: Despite repeated requests …Capablanca refused to give a clear and definitive answer to my challenge and, in his letters and telegrams gave me to understand unequivocally that it was necessary for me to come to New York if I wanted to reach an understanding with him. And second, My refusal could have been interpreted incorrectly by the chess world – that is, as a testimony of “fear” of Capablanca…”

Thus, Alekhine decided to go. He finished second, with 11.5/20, behind Capablanca who scored 14.5. The rest of the introduction to the book is Alekhine briefly covering several reasons why Capablanca isn’t perfect. In short, it seems like he had, after winning the match that took place later in the year, wanted to boast, and show Capablanca for less than he was. Given their rivalry, Capablanca’s undefeated performance at New York 1927, and the crushing, unexpected victory Alekhine orchestrated in their match (6-3 with 28 draws), it’s understandable he wanted to use the tournament as a platform for sharing his remarks.

He goes so far as to dissect every stage of Capablanca’s game, as well as every game he played during the tournament. In the introduction! Andy Soltis, in the foreword, compares the book to Nuremberg 1896, in which “Tarrasch ridiculed the victory of his rival, world champion Emanuel Lasker. At the end of that book, Tarrasch compiled a “luck scoretable”, that claimed that Lasker scored five luck acquired points from bad positions…” Never before have I seen this level of subjective writing in a chess book. They are usually dry, subjective, and, at least on surface, just.

Alekhine’s Other (Less Subjective) Books

The Participants at New York 1927

After New York 1924, the 27 tournament seems far less glamorous. The lineup consisted of 6 players; Capablanca, Alekhine, Nimzowitsch, Vidmar, Spielmann and Marshall. Alekhine notes that the tournament was arranged in a way that would give Capablanca a psychological edge, as all the participants had a negative score against him, and those who could challenge him were absent. Three players that would definitely have a say were notably absent; Rubinstein, Lasker and Bogoljubov. Bogoljubov was at his height, and he asked for a large appearance fee, and Lasker had declined to play due to an incident with the clock that happened during the 1924 tournament and that hadn’t been handled well by the arbiters.

The players who have participated were given a beating in the introduction. Alekhine focused on their play against Capablanca, of course. As he mentions, he analyzed Capa’s games while en route to Buenos Aires for the match.

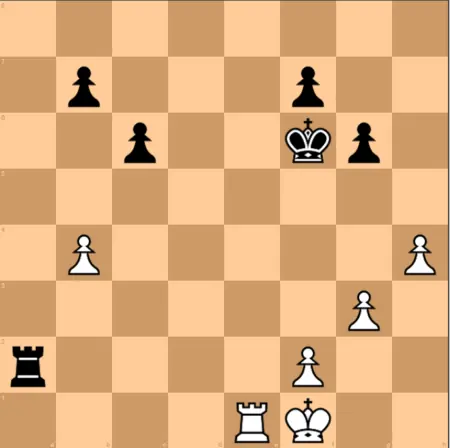

This is the round 1 game played between Frank Marshall and Aron Nimzowitsch in the scary Winawer French. This is the position on move 17 for black. How would you evaluate it? Whose attack is more promising? Is Marshall in tactical trouble or are his pieces being misplaced? Alekhine writes for this position: “The decisive mistake, because now the second player can occupy the correct queenside defense formation with gain of tempo.”

On Chessmind you can solve positional problems and get instant feedback like you would from a real coach, you can learn from numerous opening courses, practice tactics adapted to your strength, and get access to ChessGPT! Try it out!

When speaking of his own play, Alekhine lies. That’s my opinion but anything else seems unlikely. He blames the mental strain he had to endure before the tournament for his bad start, after which “I played for a draw as a result of my vulnerable tournament standing and bad shape.” He says he and Capa only played one real game, their first. Of the game, Alekhine says “Thanks to my bad play, the chess value of this game was equal to zero, the psychological value, on the other hand, enormous – not for the vanquished, but rather for the vast chess audience.” Based on that game, Alekhine continues, the chess world concluded that there would be no fight in Buenos Aires at all (at their match), but a massacre.

When introducing the games of the other 4 participants, Alekhine is unrestrained. He says, for example, “But what a helpless impression Nimzowitsch’s positional play makes! Move 16.g4 (in his first game against Capa) for example, is unworthy of even a mediocre amateur.”

Alekhine’s Annotations

Every game from the 20-round tournament was annotated. Once you get past the fact that Alekhine wrote not only to present the games and instruct, but to belittle Capablanca, the annotations are among the best he ever wrote.

He is witty, obviously very knowledgeable, and descriptive. His notes explain ideas well, which makes all of his books highly instructive. For the position from his game against Spielmann in round 2 after move 36.Re1 by Spielmann he writes: “Hardly had the rook endgame begun when white already commits the decisive error.”

He continues: “As becomes immediately apparent, the idea to defend the b-pawn from the fourth rank is quite an unfortunate one, and the intended cordoning off of the black king from the queenside is not executable.” He says that correct was 36.Rb3. The game move draws as well, but it’s difficult to see why from the current position. In reality, Spielmann made a mistake several moves later with 38.Rf4+. That move is given no notes, despite being the actual losing move.

That being said, his variations, despite being wrong in some instances, as was the case above, are valuable for humans nevertheless. They haven’t been corrected, even though the editors have gone through the games with Rybka. Usually, in Russell books, notes are added to accompany the original notes with modern evaluations. I think they’d have added value to the book. It’s up to the reader to use an engine on the side, which I did, to check on Alekhine from time to time.

I found 63 mistakes in his analysis that evaluated the position very differently to an engine. Again, the example above in which Alekhine says Re1 is an error compared to Rb3 is one of the 63. There is, however, no pre-engine era book without mistakes, and all of them should be put under the scrutiny of modern engines while reading.

Conclusion

New York 1927 is a historically significant tournament book more important as a source on the Capablanca-Alekhine match played 6 months later than the tournament itself. Alekhine wrote the book after their match and used it to be, as Soltis puts it in the foreword, “a sore winner after being a sore loser”. Alekhine’s annotations are, as per usual, great, albeit more subjective than in his other books since he targeted and highlighted every single mistake he thought Capablanca had made. The book is suitable for advanced players and will require a board to be followed easily and an engine to check Alekhine’s sometimes flawed evaluations.

Other Game Collections You Might Like

- ELO: 1800

- -

- 2000

- The Life and Games of Vasily Smyslov, Volume 1: The Early Years 1921-1948

- Andrey Terekhov