Introduction

I first learned about Smyslov in detail from Ben Finegold’s videos. He said Smyslov’s nickname was “the hand” – he always made the right move. I remember watching Ben’s lecture for the Saint Louis channel titled The Legend: Vassily Smyslov over 20 times when I began playing. I was drawn to the simplicity of Symslov’s games and how Ben managed to explain the reasoning behind moves that were, compared to Tal, Kasparov or Bronstein, well … dry.

There never seemed to be a critical position in a Smyslov game. He would just play normal moves and win. Later, when I started studying games of other players, I grouped Smyslov with Karpov, Leko, and GIri. Their style is, or was, to play the best move. No preference, no style at all really. Smyslov played what the position required of him, he had no biases towards dynamic or static, simplified positions, or those with every piece left on the board.

This is game six from the Botvinnik – Smyslov World Championship Match (1957). Smyslov had white. On move 18 for black, Botvinnik was struggling to find a good move. How would you evaluate the position?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach! Try it out!

A perfect Biography

Andrey Terekhov has managed to write the only game collection and biography that can stand shoulder to shoulder with Chess Warrior, The Life & Games of Géza Maróczy by László Jakobetz. When I first read the Chess Warrior I was blown away by the level of detail, the amount of information, and the smartly organized material. I doubted I would find an equally good book so quickly. Terekhov’s first volume of The Life and Games of Vasily Smyslov definitely exceeded my expectations.

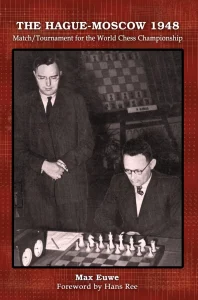

This, same as Jakobetz’s book, is both a biography and a game collection. It features 49 complete games, played by Smyslov from 1935, when he was 14, to 1948, just after the World Championship tournament in the Hague which saw Botvinnik win the title. Smyslov famously, and unexpectedly came second.

Along with the complete games, the book features many more positions. Annotated segments of games from a critical or significant position. I have come to enjoy those more than complete games, as I don’t have to spend time on openings. I always go through all the annotations over the board, so I naturally enjoy middlegames and endgames more.

About the Author

Andrey Terekhov is a Fide Master from St. Petersburg. He is Svidler’s generation. Peter, who wrote the foreword, mentions playing him in youth competitions when they were growing up. Andrey is a ICCF International Master at correspondence chess, and he holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science.

Second Volume?

The first volume covers Smyslov’s early life, from when he was born in 1921, to his participation at the 1948 tournament. Andrey writes in the introduction that the second volume would cover 1949-1957, the year he finally managed to win the World Championship title on his third attempt in a match against Botvinnik. He goes on to say that the remainder of Smyslov’s career would require additional volumes.

I tried to find information on the second volume. It has been almost 6 years since the first and I found no mention of the second coming out any time soon. I did find Andrey’s comment on a post saying that the praise he’d received for the first book motivates him to keep working on the second. The comment was from 2021.

Structure of the Book

The book is divided into 10 chapters with annotated games and positions, an additional chapter on Smyslov’s life with his wife, and two appendices. The ten chapters on Smyslov’s career are sorted chronologically, from his first games in the mid-30s, to the 1948 tournament.

Historical and Biographical Data

This is a very special book due to the amount of work and research put in, and the volume of sources, articles, letters, photos, and notes and annotations by other players presented inside. It’s not a simple game collection – it’s a treasure trove of information on Smyslov’s chess, life, as well as chess in the Soviet Union in the 30s and 40s. Again, only the Chess Warrior was written with as much love and patience out of all chess biographies I’ve ever held in my hands. Terekhov has accompanied each game and each period of Smyslov’s early career with countless citations, segments of letters, Smyslov’s own notes, annotations by his contemporaries, and mentions of him or of the events described in publications at the time. It must have taken him years to prepare all the material.

Nadezhda Andreevna

A full chapter is devoted to Smyslov’s wife, Nadezhda Andreevna. It covers their life together, from the first time they met and their first date, until their deaths, which were only two months apart, in 2010. They spent 60 years happily married.

The Smyslov Variation of the Grünfeld

There are two appendices to the book. The first is on Symyslov’s contribution to the Russian Variation of the Grünfeld. The variation with 7.Bg4 became known as the Smyslov system. The variation 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. Nc3 d5 4. Nf3 Bg7 5. Qb3 dxc4 6. Qxc4 O-O 7. e4 Bg4 was played by Smyslov several times. Terekhov gives many game examples where Smyslov had both white and black against Botvinnik, Boleslavsky, Lilenthal, Euwe, and other strong players before and after the 1948 tournament.

His final game using the system was in 1949 against Levenfish. It was a bad defeat, and during the USSR Championship, the most prestigious competition for Soviet players outside of the World CHampionship matches.. It even won a brilliancy prize awarded by Botvinnik. After 1949, Symslow switched to the Nimzo.

Smyslov’s Endgames

The second appendix was written by the German grandmaster and endgame expert Karsten Müller, whose works include endgame bibles such as Endgame Corner, Understanding Rook Endgames, and the work on several editions of Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual. It consists of 11 annotated endgames. Smyslov, known for his methodical play and excellent technique, was one of the strongest endgame players during the era of Soviet domination. Botvinnik stood next to him. No one else came close. Smyslov wrote books on the endgame, including his famous book on Rook Endings, co-written with Levenfish, and Vasily Smyslov: Endgame Virtuoso, his endgame autobiography published in 1997.

He started composing endgame studies when he was just 15 years old. Even his first ones got published in Soviet magazines. Even when he stopped playing competitive chess due to his deteriorating health, he composed studies.

Müller says: “…I want to show that endgames were already one of his major strengths when he was young. His deep understanding of endgame principles, such as activating the king, was evident in his praxis.” The appendix covers 11 endgames played between 1940 and 1947. The analysis is, as usual in Müller’s books, highly instructive.

Other Game Collections You Might Like

- ELO: 1800

- -

- 2000

- Lessons with a Grandmaster, Enhance Your Chess Strategy And Psychology With Boris Gulko

- Boris Gulko, Joel Sneed