Introduction

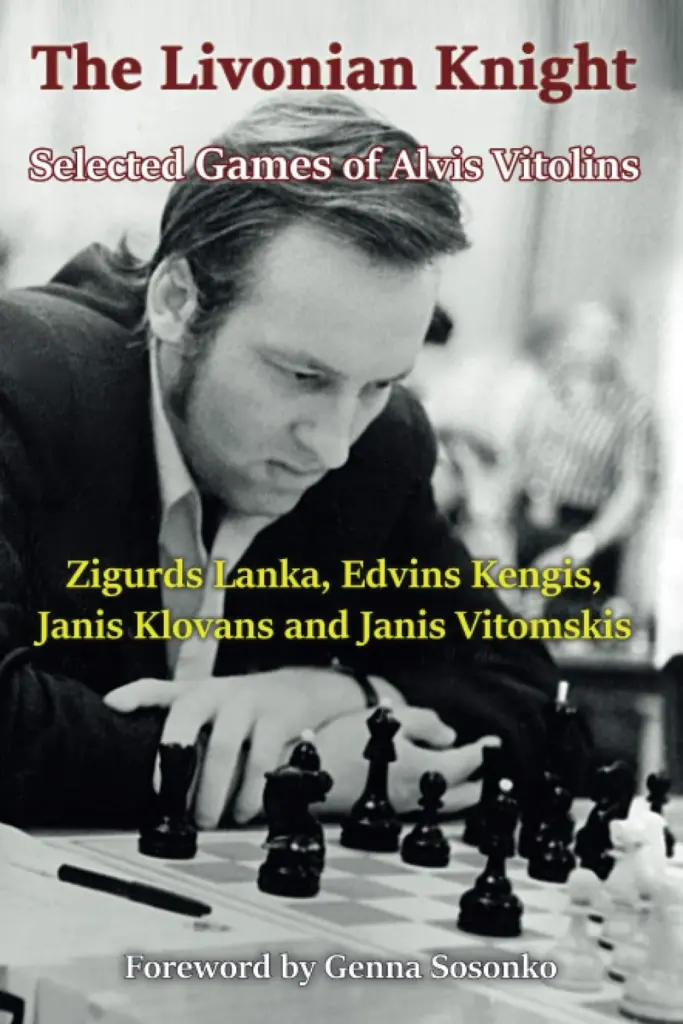

Alvis Vitolins never became a grandmaster. Despite that, his influence and legacy is greater than that of many of his contemporaries and grandmasters. He was born in 1946, learned chess at the age of 6, and began playing in serious tournaments in the early 60s.

His plateau, or his lack of GM title, is blamed on his inability to play versatile chess and to withstand the boredom of slow positions by the authors. Furthermore, Vitolins has only played a handful of open tournaments before the fall of the Soviet Union, and, by the time it collapsed, in the 90s, when he did play abroad, he was already past his peak.

When I first got the book I wondered what the adjective “Livonian” refers to. I’ve been to Latvia, and I’ve never heard the word before. This is the wikipedia entry: “Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia. By the end of the 13th century, the name was extended to most of present-day Estonia and Latvia, which the Livonian Brothers of the Sword had conquered during the Livonian Crusade (1193–1290). I’m a medieval archaeologist, so I was more than a bit ashamed to learn that Livonia is a medieval region that covered today’s Latvia, and other parts of the Baltic states, Estonia, Finland, and Lithuania.

This book is a game collection, but it focuses on a very specific part of Vitolins’ career – his contributions to chess theory. It’s divided into ten chapters, each exploring his opening ideas, novelties, and sacrifices in certain types of positions. Vitolins was a fierce attacker, and most of his ideas were ridiculously aggressive and very sharp.

It’s a very short book. Only 129 pages, but packed with thrilling games and interesting facts from Vitolins’ life and chess career.

Vitolins and Mikhail Tal, Two Latvian Attacking Geniuses

Sosonko writes in his foreword: “…we really got to know each other in the late 60s in Latvia. Back then, I regularly travelled to Latvia to work with Tal. Several times, a tall young man showed up at 34 Gorky Street, the apartment building where Misha used to live and which now bears a memorial plaque for the great champion. Vitolins’ appearance and gait looked somewhat similar to Bobby Fischer’s. Tal had a plus score in the endless blitz games they played, but Alvis still managed to beat his famous opponent numerous times, usually with quick, crushing attacks worthy of Tal himself. As I watched the games, I saw exactly what Tal meant when, during analysis, he would sacrifice material for an initiative and, rubbing his hands together, said, “And now, let’s play like Vitolins.”

Tal was born in 1936. He was 10 years Vitolins’ senior. He became the World Champion in 1960, when Vitolins was 14. I don’t know when their games took place, since the authors don’t specify, but I like to imagine that the young Alvis had access to Tal’s brilliancy and that Tal served as inspiration for his washbuckling style.

I did a bit of research and managed to find their tournament games. They played five times. Their first battle took place in Yerevan in 1980. It was a quick 17-move draw in the exchange Spanish. In the remaining four games they drew twice and Tal won twice. I couldn’t find their blitz games! They must have been unofficial.

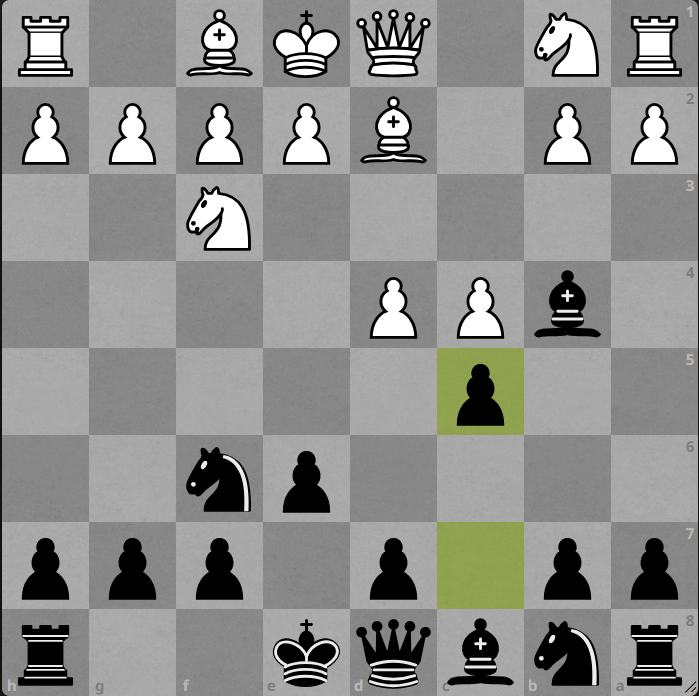

Here is a position from the game Vitolins played against Vladimir Tukmakov in RIga in 1962. Can you evaluate it properly?

Vitolins’ Contributions to Theory

The book is structured by Vitolins’ theoretical ideas. 10 chapters, each covering a certain idea or theme Vitolins introduced. His ideas were employed by the strongest grandmasters at the time, and tested on the elite level. He is a rare non-grandmaster who had several variations named after him.

I first heard of Alvis Vitolins when I was preparing my Bogo-Indian theory series. His idea of playing 4…c5 is what we know as the Vitolins Variation.

His most famous novelty may be playing 6…b5 in the classical Nimzo. 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.Qc2 O-O 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 is a position in which most people used to play 6…b6. Vitolins introduced b5! I think the common name for this gambit today is the Vitolins-Adorján Gambit. His idea wasn’t only applicable in one move order. He also played it on move 5. 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Qc2 O-O 5. Nf3 b5 is known as the Nimzowitsch-Vitolins Gambit.

Vitolins introduced a mad attacking idea in the modern Alekhine, known today as the Vitolins attack or the Vitolins Gambit. After 1. e4 Nf6 2. e5 Nd5 3. d4 d6 4. Nf3 Bg4 5. c4 Nb6, where exd6 or the simple Be2 are the main move, he introduced 6. d5! A brilliant disruptive sacrifice (that should not be taken) with deep strategic ideas behind it of a queenside pawn advance with a4-a5, misplacing black’s already awkward Alekhine knights.

Vitolins has had many other opening ideas work with greater or lesser success. Many of them have been adopted by grandmasters and are still played today.

His sacrifices in the Sicilian are not exactly theory, but they’ve become a staple in any attacking player’s e4 repertoire. He was famous for sacrificing on b5, d5, and e6, just like Tal. A whole section of The Livonian Knight is devoted to his attacking and opening ideas as white against the Sicilian. One can’t help but confuse his games with Tal’s games.

Structure of the Livonian Knight

The book is divided into ten chapters. Each chapter follows a specific opening, variation or theme Vitolins has contributed to. In the first chapter, “Wedge in the center of the board”, the authors cover the Vitolins Gambit in the Alekhine.

The second, titled “Is it always safe to castle?”, is devoted to early problems in the French and the Caro-Kann. Chapters three to seven are devoted to the Sicilian, and they cover his famous ideas such as the piece sacrifice in the Poisoned Pawn Najdorf, or his attacking ideas in the Richter-Rauzer. Chapter eight covers his unconventional way of playing the Spanish.

Chapter nine covers the Bogo and other closed positions, and the final chapter the authors analyze his famous gambit in the Nimzo.

Each chapter consists of one or two annotated games. The chapters aren’t long, and neither is the book.

Quality of Annotations

I’m not impressed with the amount of annotations. Most of the games were annotated very briefly, with many variations lacking text completely. The goal was to highlight Vitolins’ style and theoretical ideas, so that’s what the authors have focused on, but I feel like they could have done much more.

The book is 129 pages long. I think, had it been properly annotated, it could have been twice as long or even longer.

That being said, the annotations are good.

Difficulty and Rating Range

The Livonian Knight, same as most game collections, is an easy read and not a workbook. I’m 2000 fide and I couldn’t follow it without a board simply because the annotations aren’t detailed.

I think anyone, regardless of rating, should be able to go through it without too much trouble if using a board on the side. Ideally, you should be at least 1600 in order to understand all the ideas presented in the book.

Conclusion

The Livonian Knight is a remarkably fresh collection of chess games of an unknown chess genius. It depicts Alvis Vitolins’ playing style, his contribution to theory, and his remarkable ability to create dynamic complications regardless of his opponent’s strength. It is not perfectly annotated, so it’s best suited for players over 1600, as it may be difficult to follow for beginners.