Introduction

If you’re reading this, you are probably trying to get better at chess. Chess books remain the most valuable training resource at our disposal.

Chess Books aren’t Harry Potter. They are instructive manuals meant to develop your chess skill, not provide pleasure (although there are those that do both). I’ve tried to explain how to use them effectively.

Stefan Zweig wrote in The Royal Game: “In chess, as a purely intellectual game, where randomness is excluded, – for someone to play against himself is absurd … It is as paradoxical as attempting to jump over his own shadow.”

And yet, that is what we have to do while reading chess books. We must play against ourselves in order to fully immerse ourselves into the material.

Should you use a board to set up positions from the book? Should you move the pieces while analyzing? How much time should you spend per position? Is it normal to spend an hour on just one page? I will answer all these questions and everything else you need to know to get the most out of reading chess books.

Books Compared to Other Training Material; Courses, Videos, Online Tactics…

One rule always applies – there is no progress without effort. Passive consumption of content will not improve your skills. That is why active methods – playing, analysis, solving problems, and reading, are the best way to improve at chess.

Books are, in my opinion, the third best learning resource after playing and analysis. They allow you to recreate tournament conditions and consuming them properly involves every aspect of proper chess training.

Compared to online courses, they are vastly superior for over the board, tournament play simply because you set up the pieces over a board when reading, which is how you see chess during tournaments.

Online Tactics vs Problems From Chess Books

We all solve tactics online. It’s an easy and always available form of training. Sometimes online problems are great, but more times than not, they are generated problems from online games or AI generated puzzles.

Puzzle books and all chess books that provide problems for the reader to solve have five important advantages – firstly, the problems are carefully curated. They are hand-picked by grandmasters for a reason. Either they reinforce the lesson from the book and are meant to teach a specific pattern, or they are chosen for a different reason.

Secondly, the solutions are annotated. When you fail a tactic online the only feedback you get is that you were wrong and what the solution actually was. In books, you get a detailed explanation of the idea, often including several mistakes you may have committed and explaining why they were incorrect. Being able to hear a strong player explain a problem is the true value.

Thirdly, when you solve problems from books, you do that over a real board and recreate tournament conditions. Granted, you could do that with online problems too, but almost no one does that.

Furthermore, online problems often focus on a single theme or type of problem – you are better and have to win or mate. Books offer a variety of themes. Finding strategic or positional problems online is difficult, and you could just take 400 Chess Strategy Puzzles, and have a selection of hand-picked problems different to anything you could find online and completely devoted to strategy.

Lastly, online problems are infinite. You can do them forever and it doesn’t matter how many you solve or how many you fail. Books are limited, and there’s a sense of accomplishment when you solve a tactic from a book. You don’t rush, and you take each problem seriously.

How Can You Tell a Good Chess Book from a Bad One?

“Some books should be tasted, some devoured, but only a few should be chewed and digested thoroughly.” ― Sir Francis Bacon

There is one simple way to tell whether a book is good or not – the annotations. All the reviews on Chessreads always feature the quality of annotations. Why? Because a book with poor annotations may as well be a PGN file.

There are many other factors that determine the quality of a chess book, of course, but the quality and quantity of text is the decisive factor.

I could name books that were completely useless, or books that were more useful than lessons with my coach, simply based on the annotations.

Old Classics vs New Books

“′Classic′ – a book which people praise and don’t read.” ― Mark Twain

Everyone says we should study the classic games and read the classic books such as Zurich 53, St. Petersburg 1909 or Montreal 1979. We should, but they shouldn’t take precedence over new books simply because they are old or famous. There are, in fact, many examples of classics which are not very useful, such as Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess.

There is no difference between classics and new editions. If a book is good, it’s good.

Training vs Reading

“′Books are the training weights of the mind.“ ― Epictetus

Many people don’t know how to read chess books. Then there are others who choose to read them “the wrong way”. I read chess books two different ways, depending on the situation – for pleasure and for study. Training and reading are very different.

When I want to enjoy a bedtime story, I may pick up a game collection and read through a game without doing my own analysis.

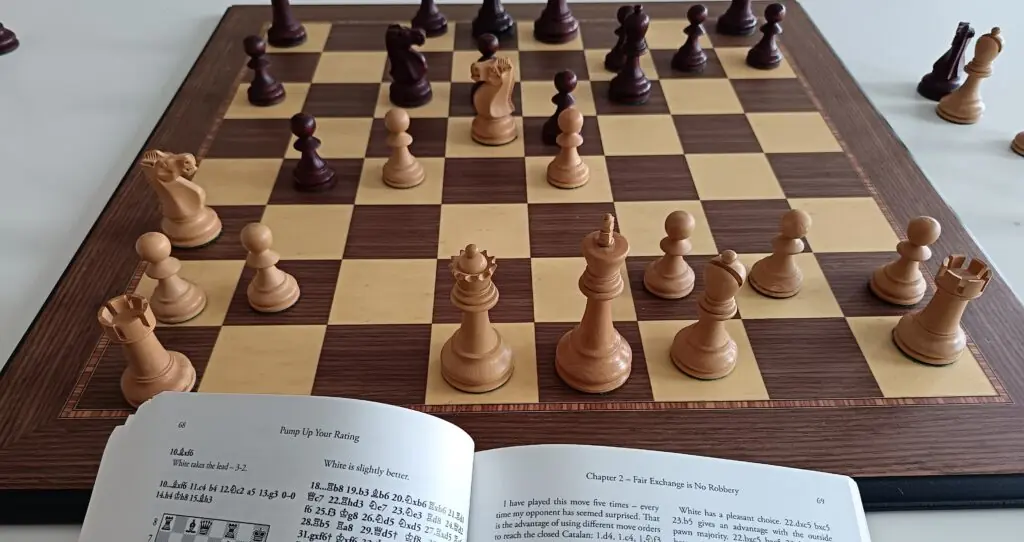

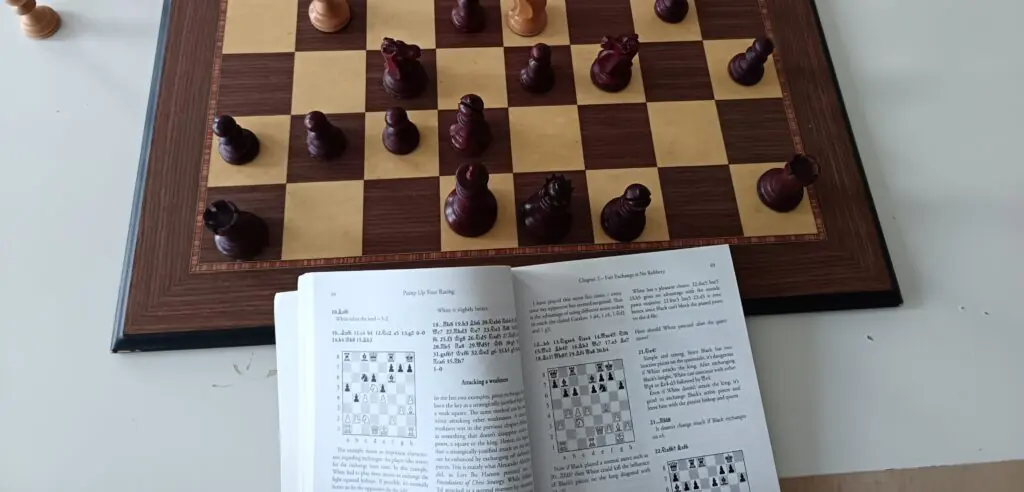

When I train, or prepare for a tournament, I train hard. I set up every diagram on the board, I follow all the sidelines, I do everything without moving the pieces. Why? Because I’m training for over the board play, and I’m trying to recreate tournament conditions.

Use every book you plan to learn from this way. There is no progress without getting engaged and putting in the time.

Time Spent Per Page

People often ask me whether it’s normal to spend an hour on a single page of a chess book. It is! Maybe you are 1200 rated, and you’re reading Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual. Well… Either you’re lying to yourself by going through the book quickly, or you’re being honest, and it takes you an hour per page.

The goal isn’t to read as many books as you can quickly. The goal is to learn. To correct the mistakes in our thinking processes and to accumulate knowledge.

You have to be curious, analytic, and relentless. Don’t give up until you understand everything. Set up every position and never move the pieces. And if it takes you a year to go through one book? So what! You will have gained immense experience by doing so.

Does Your Rating Change The Way You Should Use And Read Chess Books?

Absolutely not. Whether you’re a GM or a 1000 rated player, you need to invest time into every page and every position until you fully understand it. The only difference will be the amount of time spent. A Grandmaster may spend 3 minutes and you 3 days.

Using a Chess Board While Reading

This is the key to reading chess books properly. You’re not reading Sherlock Holmes. You are training! Imagine going to the gym and watching a guy doing pull-ups. That wouldn’t make you stronger, would it? It would also be pretty weird. You have to do the work yourself. No amount of reading will help if you don’t.

When reading a book, I always have one or two boards next to me. I will go through the main lines on one, and do my own analysis on the other. If I’m travelling, I will use a small set. Why do I do this? Because it allows me to recreate tournament conditions and use my brain the same way I would during a game.

Don’t hesitate to go beyond the author’s analysis and explore the lines they haven’t mentioned. Curiosity is a trait of every strong player.

Moving the pieces should be reserved for after your first analysis. Always train without moving them first. If you fail to solve a position or are stuck, move them. That makes the process much easier, of course.

Different Categories of Chess Books

Different chess books require different approaches. I’ll explain how to read books in each category effectively.

Endgame Books

Endgame books can be divided into theoretical, complex endgames and puzzle books and studies. Puzzle books should be solved the same as all other puzzle books.

Theoretical endgame books should be used as an index of positions you have to know. I use them to go over endgames from my games and focus on those I didn’t play well. Before that, of course, you have to master the basics. I would advise you to take any theoretical endgame book, such as 100 Endgames You Must Know, and play out the basic endgames. Against an engine if you don’t have a sparring partner, but ideally against a human. Reading about a theoretical endgame is almost useless. You have to test your skill.

Complex endgames are a different story. Books that cover them are closer to middlegame books than to theoretical endgame books. They often cover complete endgames and require you to go over the analysis on a board and follow the annotations.

“′He examined the chess problem and set out the pieces. It was a tricky ending, involving a couple of knights. ‘White to play and mate in two moves.’

Winston looked up at the portrait of Big Brother. White always mates, he thought with a sort of cloudy mysticism. Always, without exception, it is so arranged. In no chess problem since the beginning of the world has black ever won. Did it not symbolize the eternal, unvarying triumph of Good over Evil? The huge face gazed back at him, full of calm power. White always mates.“ ― George Orwell, 1984

Opening Books

Opening books are specific. I would advise you to use them carefully and moderately. Most are poorly annotated, especially those written before 2000. There are very useful exceptions, such as Squeezing the Gambits, that offer detailed annotations and cover plans instead of endless variations.

Most opening books should be used as indexes and not read as books. I go over them during tournaments and when I’m preparing. I will go through 20 books on the Caro-Kann simultaneously to compare the ideas. I will read the chapter on the Tal variation from each of them if I know that that’s what my opponent will play.

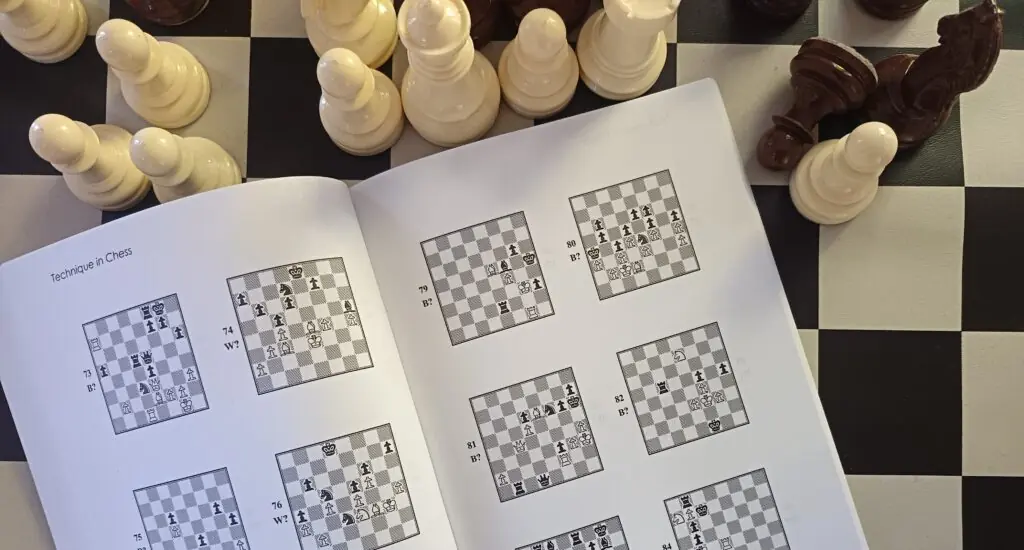

Puzzle Books

Puzzle books are chess books in their purest form. Set up every problem on a real board, don’t move the pieces, time yourself, and repeat every problem you’ve failed.

The problems you fail will be more useful than the ones you solve successfully because you will learn from the annotated solutions and correct your thinking processes.

Books on Strategy, Positional play, Thinking Processes and Planning

Middlegame books come in different forms. There are books that lean more towards theoretical knowledge and explaining concepts, and those that are based on application of skill. Most are a combination of the two.

They should be read using a board, as always, and writing down everything you weren’t familiar with beforehand. I use notebooks to track how my library of patterns increases over time. Say you’re reading a book on dynamic vs static structures, and you encounter an e5-push in the Benoni you’ve never seen before or didn’t understand – catalogue it! You don’t have to use notebooks, normal people do that online. I’m not normal.

Books on Calculation and Tactics

Books on calculation are not puzzle books. They explain how to calculate. Take Kotov’s Think like a Grandmaster, one of the earliest attempts to explain how calculation works. He introduced his famous tree of variations, which people still reference today. It’s partially a workbook too, with problems to solve, but it mainly focuses on how to solve them, and the process behind calculating effectively.

Each book in this category should be taken with a grain of salt. Our brains work differently, and we all calculate differently. There is no uniform, optimal way to calculate, nor can anyone teach someone to replicate their exact thinking process. That is why you should take bits of useful information from tactics books and not take them literally.

Game Collections

Game collections are a combination of all the above categories. Apply all the advice I’d written previously and follow all the games as if you were solving problems, learning endgames, openings, and strategy. Game collections, tournament books and biographies are also light reads compared to workbooks. So enjoy yourself! I read them when I want to unwind before bed.

“I prefer to make my annotations ‘hot on the heels’, as it were, when the fortunes of battle, the worries, hopes and disappointments are still sufficiently fresh in my mind. Much as I would like to, I cannot say this about these few games which will be given below. In fact, if the annotator should begin to use phrases of the type: ‘in reply to…I had worked out the following variation…’, the reader will rightly say ‘Grandmaster, you are showing off’, since the ‘oldest’ of these games is now more than 25 years old, and even the ‘newest’ more than 20. Therefore, I would ask you not to regard the following ‘stylised’ annotations too severely.“ ― Mikhail Tal, The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal

Rereading Chess Books

“′If one cannot enjoy reading a book over and over again, there is no use in reading it at all.“ ― Oscar Wilde

You’ll often hear Grandmasters say that they’ve read their favorite book dozens of times. I have reread every Sherlock Holmes story at least five times, and I always find something I’d missed on my previous reads. Imagine how many new things you’d discover if you went over the same chess book five times.

Chess books are training material, and it’s very useful to go over them many times. Even puzzle books can be solved multiple times. The Woodpecker Method is built on that principle!