Introduction

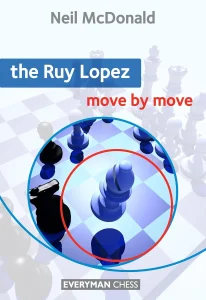

The Zaitsev System by Alexey Kuzmin is a wonderful book. Not just a wonderful chess book, or an opening book, but a wonderful book. I read it while preparing the Spanish series on the Hanging Pawns channel, and I was expecting a boring read full of variations, which is what you normally get from an opening book. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. Kuzmin has written one of the best, most detailed, most descriptive, and most entertaining opening books of all time. I would go as far as to put his Zaitsev System alongside my favorite opening book, Squeezing the Gambits. To put things into perspective, Kuzmin is a Russian GM, and he used to work with Karpov from 1987 to 1991. He was Karpov’s second during the matches with Kasparov. And Zaitsev, the inventor of the system, was who Karpov learned the opening from. So Kuzmin is one of the biggest experts on the opening in the world and he has first hand experience from his prep sessions with Anatoly Karpov.

Kuzmin’s First-Hand Experience with the Zaitsev System

Kuzmin writes in the introduction: “I began seriously analysing the Zaitsev System back in the second half of the 1980s, when I joined Anatoly Karpov’s training team. After that there was a gap of about fifteen years. Of course, I followed the development of ideas in this variation that I had come to like, but I largely followed it like a spectator, who sits in a theatre and tries to grasp the latent context in the development of the plot. I returned again to analytical work in 2006 after the Olympiad in Turin. Alexander Morozevich invited me to begin working with him as an assistant, and the Zaitsev System was part of his opening repertoire. Eighteen months ago our chess collaboration came to an end. Morozevich sharply curtailed his number of tournament appearances, and I (by mutual agreement) decided to generalise the analytical work done on the Zaitsev System and present it in book form.” (Kuzmin 2016, 15)

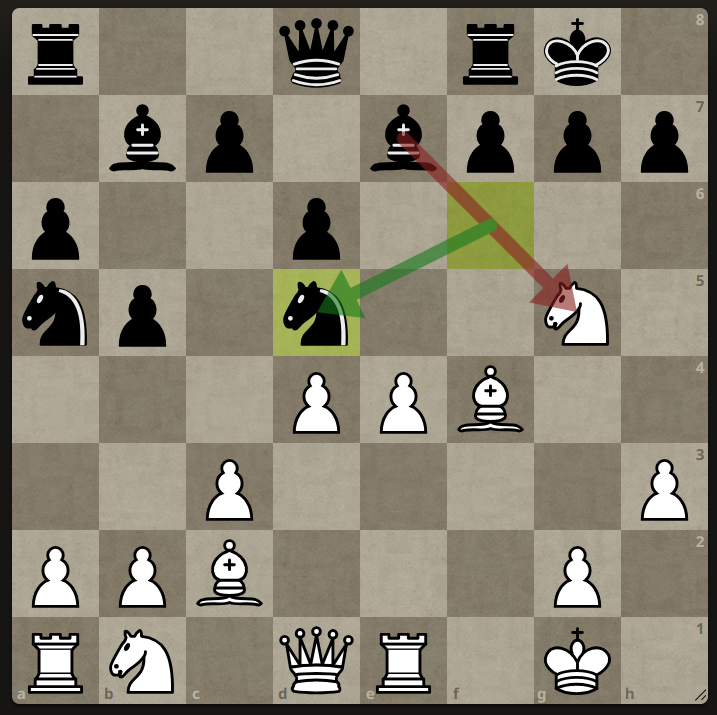

This position is from the game Kryvoruchko-Polgar from 2012, Black’s last move was …Nc4. What do you think of this position?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach!Try it out!

Igor Zaitsev is still alive. He is 87 years old. His contribution to chess theory is vast, and the Zaitsev System, an improvement to the old way of playing the Closed Spanish for black, h6, preventing Ng5, the so-called Smyslov Defense, is still a main-line variation today, almost 60 years later. His analysis not only stood the test of time, but it became one of the main battlegrounds in the Karpov-Kasparov world championship matches from 1984 to 1990. Karpov used it in every match, with an exception of the 1990 match where he used the Nd7 novelty (now called the Karpov variation) alongside the Zaitsev System. Zaitsev became one of Anatoly Karpov’s coaches in the late 70s, after the death of Karpov’s previous coach Semyon Furman. He was one of Karpov’s seconds in all of Karpov’s World Championship matches against Kasparov.

What is the Zaitsev System?

The Zaitsev, the moves 9…Bb7 and 10…Re8 (or vice-versa) was a new, improved system in the Closed Ruy Lopez based on a tactical idea that proved that h6 (Smyslov’s main line in the Closed Spanish) was in fact an unnecessary prophylactic move, and that black can start putting pressure on white’s e4-pawn immediately with Bb7 and Re8 without having to worry about Ng5.

Zaitsev writes in the foreword to Kuzmin’s book: “In the 1960s, when analysing similar games in the Ruy Lopez, including my own, I formulated on the pages of the newspaper Shakhmatnaya Moskva an important general idea for such constructions, which boiled down to the conclusion that on the basis of positional requirements in most cases in the opening stage it was much more advisable for Black to put pressure on the e4-point than to undermine it. Therefore, adhering to this principle, already at any early stage Black should in the shortest number of moves (…Bb7, …Re8) try to create the maximum pressure on the leading central outpost pawn on e4, thus tying down the opponent’s forces to its defence, and thereby preventing White from mobilising his queenside reserves in the normal way. But in this case the fate of the entire set-up depended primarily on the correctness of a little tactical trick which I had devised: which was after 9.h3 Bb7 10.d4 Re8 against the obvious attack 11.Ng5 to respond with a counter-stroke, 11…Rf8 12. f4 exf4 13. Bxf4 Na5 14. Bc2 and now 14…Nd5! A tactical stroke which, as it soon transpires, makes the two sides’ chances equal.” (Kuzmin 2016, 11)

Is the Zaitsev a Forced Draw?

Today, the Zaitsev is considered to be a “drawish” line, since white can choose to actually go for the equal endgame. So most players who have to play for a win with black avoid it and go for the Chigorin or the Breyer instead. Kuzmin does provide a weapon against the draw in chapter 6, called the Saratov Variation (10…Nd7 instead of Re8, not undefending f7). I’m not fully convinced black is doing well in those lines.

Kuzmin writes: “For those who have placed their opening choice on the Ruy Lopez, who prefer

play which avoids the early queen exchange of the Berlin Defence and the long, forcing lines of the Marshall Attack with their drawing tendencies, the Zaitsev System is an almost ideal choice.

Why ‘almost’? The answer is simple. First, the Zaitsev System still has to be obtained. A natural consequence of the popularity of the Marshall Attack and the Berlin Defence has been the universal development of lines of the Ruy Lopez with the seemingly unpretentious, but quite

venomous move d2-d3. Second, in the Zaitsev System the player with white has the possibility by 11.Ng5 Rf8 12.Nf3 of either forcing a draw, or obliging his opponent to make a different

choice. How to solve this problem is something that we examine in Part Six — ‘The

Saratov Variation’. And third, an absolutely ideal choice simply does not exist…” (Kuzmin 2016, 20)

The opening has four main systems that branch out on move 12 for white. The old main line is 12.Bc2, called the Geller-Karpov variation. In the 80s, Kasparov introduced 12.a4, 12.a3, the Sochi variation is a sideline, and 12.d5, the Modern Variation is a new weapon against the Zaitsev introduced by Short and other strong players in the 90s.

The Rich History of the Zaitsev and Kuzmin’s Incredible Knowledge

One thing that makes this book stand out among hundreds of other chess opening books, which tend to be dry and boring, and difficult to read, are Kuzmin’s introductions to each chapter and each line. They aren’t a few sentences long, but actual articles on the history of each variation, when, how, and why it began being played, and what the ideas behind it are and who is responsible for developing them.

Looking for an easy way to learn openings and build a repertoire? With Chessbook you can find the gaps in your repertoire before your opponents do. You will only spend time on the moves you’ll actually see, learn middlegame plans for any opening, and easily find mistakes in your online games. Connect your Chess.com or Lichess account to get instant feedback when you deviate from your repertoire. Try it out!

Each of the 6 main parts of the book are given a historical introduction. I enjoyed them greatly! In the chapter on the 12.a3, the Sochi variation, Kuzmin writes: “In the numerous bars champagne flowed, snow-white beer foamed, and Armenian cognac sparkled in fat rounded glasses. Sunning themselves on the beaches were the Irina Shayks and the Kournikovas of the 1970s, encircled by tanned ‘machos’’ engaged in a predatory search for their next victims, and romantic couples strolled unhurriedly along the shaded alleys. And all this was shrouded in a magical aura of mystery, abundance and prosperity.” (Kuzmin 2016, 82). He paints the picture of Sochi in the 70s as if he were Agatha Christie. I enjoyed his writing, and his style makes the book wonderfully unique.

You can feel that Kuzmin was actually a part of the Soviet world in which Zaitsev developed his system. Kuzmin has insider information that not many authors possess. When have you read an opening book in which the author provides detailed information on how and why each sideline came about? Not only is his book incredibly valuable from an instructive standpoint, but it’s a great historical source as well.

Structure of the Book

The book is divided into 6 main parts. The first four cover the 4 main variations of the Zaitsev (12.a4, 12.a3, 12.d5 and 12.Bc2). Part 5 is devoted to sidelines, and part six to avoiding the forced repetition with 10…Nd7. Each chapter is subdivided into variations, themes, or typical plans. The structure is very easy to follow and very logical.

The Annotations

They are almost perfect. Rich, detailed, descriptive, referencing important sidelines and games, and written for humans. Since the Zaitsev is a complex system that starts on move 9 or 10, you can’t expect Kuzmin’s annotations to be suited for beginners, though, so they are tough to understand unless your strategic understanding of Spanish structures is good, but that’s ne nature of the opening he covered.

Conclusion

Kuzmin’s Zaitsev System is one of the best opening books ever written. It covers everything. It was written for humans and the annotations are rich and descriptive. The historical backgrounds given to each variation add a lot of value to the book and make it an enjoyable read. A must-read for any Spanish or 1…e5 player. 10/10!