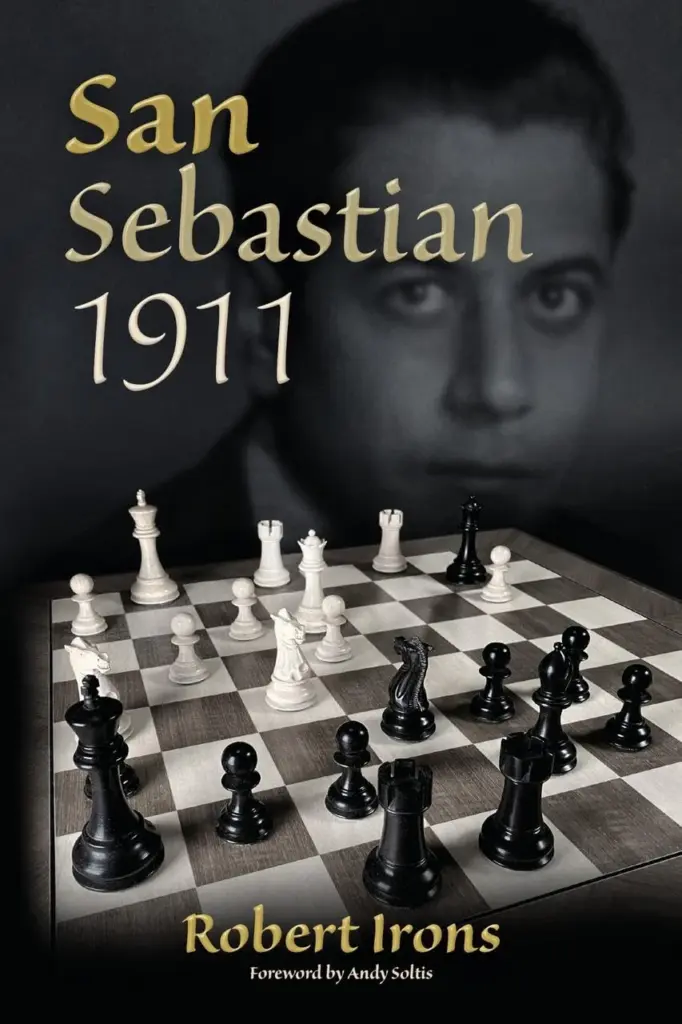

Introduction

San Sebastian 1911 was the first super-tournament. As opposed to previous major chess events, starting with the London Exhibition in 1851, all the way up to Cambridge Springs 1904, the San Sebastian tournament was elite in every sense of the word. Each prior event lacked something. Either the line-up didn’t consist of all top players, the prize fund was lacking, or the venue, the accommodation, or the playing conditions were suboptimal.

San Sebastian had it all. It was held in the Grand Casino. It was normal at the time, just as it is today, that rich resorts want attractions for their customers, thus they’re the only ones able to put up an amount large enough and accommodate the players well enough to organize an event of this scale so well.

Organized by Jacques Mieses, who himself had been a top-25 in the world player, the event was flawless. A detailed copy of the tournament regulations provided in the book proves that even the technical side of play had been prepared and arranged meticulously. Mieses published a book covering the tournament in the same year, using the original analysis of the players, his own comments, and those of other strong players whose chess notes were being published in Europe at the time. A second edition came out shortly after WWI, which is the first time a tournament book had ever been reprinted.

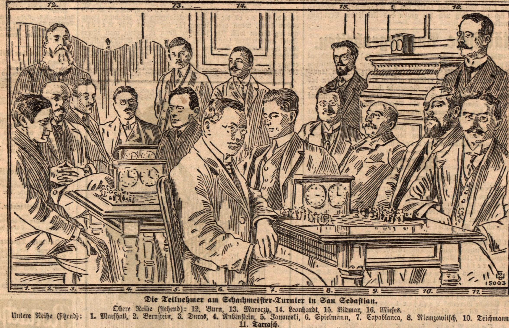

The Players at San Sebastian 1911

The field in San Sebastian consisted of 9 of the 10 strongest players in the world at the time (using a metric I don’t quite understand that attempts to determine historical ratings of chess players). Only Lasker, the world champion, didn’t participate – he was busy getting married.

The star of the show was the young Capablanca. Tournament organizers had a rule for invitees – they had to have earned at least a fourth place in at least three international tournaments in the 10 years leading up to San Sebastian. Capablanca had never played an international event before. How then, had he been allowed to participate?

Robert Irons, the author, gives two original chapters in the book, while the rest is a translation of Miese’s original work with additions of notes and annotations by other strong players and engine analysis. One of the two chapters, titled “The Case for Capablaca”, attempts to answer that question. Irons provides detailed accounts of everything said and done on the matter in the years leading up to the event. In short – with a few exceptions, not many participants had objected to Capablanca’s participation, and Mieses wanted him to compete. In light of Capa’s crushing victory over Marshall in 1908 (8-1 with 14 draws), it was clear that the invite had been well deserved.

Other books on Capablanca you might like:

Irons gives a short comment on the topic given by Capablanca himself in his book My Chess Career: “The conditions of the tournament made it the best that could be had. It was limited to those players who had won at least two third prizes in previous first-class international tournaments. An exception was made with respect to me, because of my victory over Marshall. Some of the masters objected to my entry before this clause was known. One of them was Dr. Bernstein. I had the good fortune to play him in the first round and beat him in such a fashion as to obtain the Rothschild Prize for the most brilliant game of the tournament.”

It was Manuel Márquez Sterling, the owner of the San Sebastian Casino, a chess player, and a chess patron, who actually made sure Capablanca participated. He invited Capablanca, a man virtually unknown in Europe at the time.

The rest of the field consisted of 14 masters. With the exception of Emanuel Lasker, every elite player of the pre-war era was there – Rubinstein, Vidmar, Marshall, Tarrasch, Schlechter, Nimzowitsch, Bernstein, Spielmann, Teichmann, Maroczy, Janowski, Burn, Duras, and Leonhardt.

At the time, Nimzowitsch was 25, and his modern and hypermodern ideas in chess were beginning to take shape. He introduced the King’s Indian Attack against the French and Nf6 against the open Sicilian during the tournament. It was revolutionary. Rubinstein was already considered to be a strong contender for Lasker’s crown and one of the strongest players in the world. Marshall was the only truly strong American except for Capablanca, who had moved to the US 6 years before. Vidmar, Spielmann, Tarrasch, and Schlechter were also at their peak. Out of all 15 players, Amos Burn, the English master, was the only one past his prime.

The Games

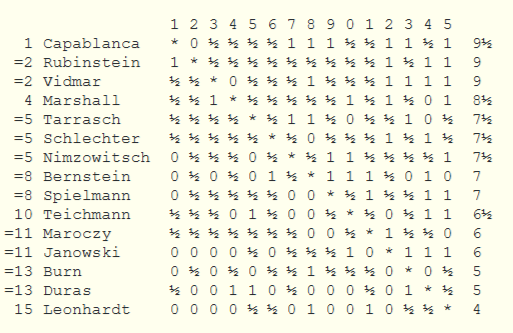

San Sebastian was a single round-robin tournament consisting of 15 rounds. In total, 105 games were played. All 105 games are annotated in the book. Irons has not written or annotated San Sebastian 1911. He provided engine analysis, and he compiled notes by other strong players, like Andrew Soltis, Donaldson, Emanuel Lasker, and Capablanca to accompany the original annotations by Jacques Mieses, that had been published in the two original German editions in 1911 and 1919.

Here is a famous position from the game Nimzowitsch – Capablanca, St. Petersburg 1914. I chose this game, even though it hadn’t been played in San Sebastian, because it showed Capablanca’s true genius. Can you evaluate it properly?

Chessmind is a great learning platform where you can answer positional questions and get instant feedback. It recreates lesson conditions, and comes close to having a chess coach! Try it out!

The final result of the tournament wasn’t surprising. Capablanca won, with Rubinstein and Vidmar finishing half a point behind.

The Annotations

Robert Irons isn’t to be blamed for the lack of quality annotations. It’s Mieses, whose original text was used as the basis for this modern edition. The translator of the new edition from German, Gerard Nielsen writes:

“To wit, while there is poetry in the game of chess, there is very little poetry in the reporting of the game of chess.” I would disagree with that! There are many chess books in which the annotations are as exciting as a mystery novel. Fine, I’m a nerd and exceptionally fond of chess, but I truly think so. I would point out New York 1924 as a great example.

Nielsen continues: “Jacob Mieses,(known later in life as Jacques Mieses), was by every measure a chess grandmaster and by those same measures a dry-as-dust writer. Luckily, for us, here in the second edition of the San Sebastian report, he adds some wit and wisdom to the original. The first edition had to be out as soon as possible in order to both recoup some of the expenses of the tournament and to teach those who could not be there the ways of the greatest players in the world.”

Mieses’ annotations, even those from the 1919, updated, more detailed, 2nd edition, aren’t great or very detailed. Do the math yourself – 105 annotated games covered in 234 pages. That’s just over 2 pages per game. I may be spoiled, but I consider fully covered games, where almost every move of the game itself is annotated, with many sidelines and reference games given to be good annotations. San Sebastian was played before the first serious tournament books came out, again, New York 1924 is a great example, where Alekhine provided first detailed coverage of a tournament. The two books are vastly different. Mieses fails to cover the chess in required detail that would make the book highly instructive for the reader.

The book isn’t bad, though. The annotations, especially having been supported by notes by other players and engine evaluations explained by the author, are still valuable.

Difficulty and Recommended Rating

San Sebastian 1911 is an easy read if you want to skim through the games. If you want to be detailed, and study the games properly, you will have to set up everything over a board and struggle with the help of scarce comments by the author(s). Game collections without detailed annotations are best suited for advanced players, which is why I think this book is intended for those 1600 FIDE and over, ideally around 2000.

Conclusion

San Sebastian 1911 was a historically very important tournament. It marked Capablanca’s debut on the international stage, and a shift in generations among the chess elite, with Nimzowitsch, Rubinstein, Capablanca, and other young players, slowly overtaking the old guard. It was the first elite tournament in the true sense of the word, with 9 out of 10 of the strongest players in the world participating. Robert Irons used the original tournament book, written in 1911 by Jacques Mieses, and its second edition from 1919 as the basis for the book. He added notes by other strong players and his own comments, accompanied by Stockfish evaluations. It’s not a perfectly annotated book but it’s the best resource we have on this important event.

Other tournament game collections you might like:

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- Carlsbad International Chess Tournament 1929

- Aron Nimzowitsch