Introduction

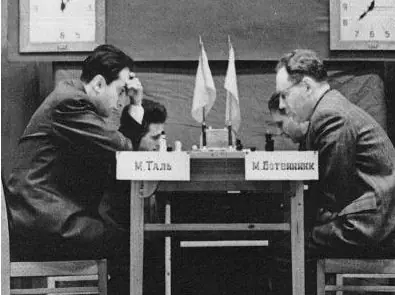

Botvinnik was born in 1911. He became world champion in 1948, after a quadruple round robin tournament held by FIDE after the former World chess champion Alexander Alekhine died in March 1946. Botvinnik won convincingly over Smyslov, Keres, Reshevsky and Euwe. At the time, Keres, who was 32, and Smyslov, who was 27, were the young, up-and-coming players. Euwe was 47, and Reshevsky 37, same as Botvinnik. That meant that Mikhail Botvinnik became the champion without a match.

I have recently finished Alekhine’s Odessa Secrets. There you can read about how Botvinnik had finally managed to arrange a match against Alekhine a day (!) before his death in Portugal. Alekhine was found dead the next morning. Many people, including the author, still speculate on the circumstances of his death.

“Chess is the art of analysis.” – Botvinnik

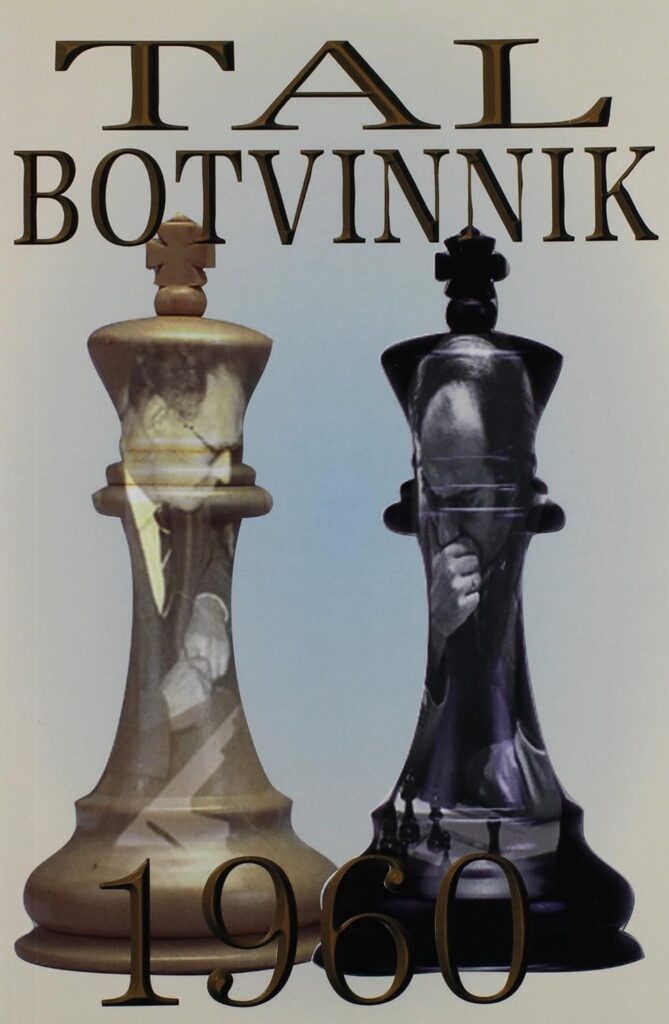

Botvinnik held the world title, with just two brief interruptions (losing to Smyslov in 1957, and in the 1960 match to Tal), for the next fifteen years, during which he played seven long world championship matches.

“You must take your opponent into a deep dark forest where 2+2=5, and the path leading out is only wide enough for one.” – Tal

Mikhail Tal was born in 1936. At the time of the 1960 match he was 24. Botvinnik, who was nearing 50, couldn’t have been more different to the young Latvian. Tal was aggressive, impulsive, and he relied heavily on his calculating abilities, entering complications whenever he could. Botvinnik was calm, calculating, he relied heavily on analysis and preparation, and preferred simple, technical positions.

“Mikhail Tal’s splendid account of his world championship match victory is one of the masterpieces of the golden age of annotation – before insights and feelings and flashes of genius were reduced to mere moves and Informant symbols. This is simply the best book written about a world championship match by a contestant. That shouldn’t be a surprise because Tal was the finest writer to become world champion.” – From the Foreword by Andy Soltis

The Match in Tal’s Words

Tal-Botvinnik 1960 is a wonderful book for two reasons. Firstly, Tal’s analysis and annotations are sublime. Each move is covered and his expertise is clearly visible from the text. Secondly, Tal’s introductions to the match and to each round.

The book begins with Tal’s “before the match” chapter, where he shares his feelings, thoughts, fears, and preparation. His match strategy and his approach to the games is something every tournament player would enjoy reading about. His introductions to each game are remarkable too. He talks about his preparation, how he and his coach have prepared and which strategy they’d decided to employ, his feelings before the game, and his conclusions. Hearing a world champion talk about the details of each game in such depth is almost unique.

Other books written by Mikail Tal you might like:

The Games

Tal covers all 21 games played during the match. He explains every idea and every move, and he shares his analysis, comparison to other relevant games, his opening knowledge, his prep, and much more.

This is by far the best annotated game collection (along with Learn From The Legends by Marin) ever written.

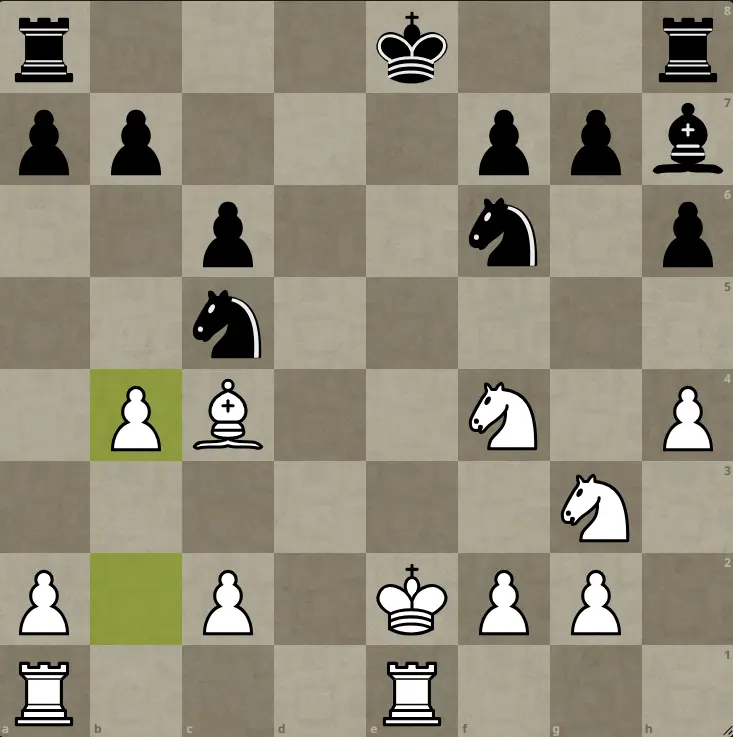

The games themselves are thrilling. Most of them have become classics, and I doubt you’ll be unfamiliar with them. Tal’s famous 5.gxf3 from game 3 in the Two Knights Caro is a move analyzed in over 50 books. So is his 21…Nf4! From game 6.

Their 1960 match is a great mirror into theory at the time. Their struggle to choose openings and defenses is described by Tal before each game. Botvinnik had started with the French in round 1, lost, and then stuck to his reliable (or so he thought) Caro-Kann for the rest of the match with black. Tal switched from the KID to the Nimzo and back against Botvinnik’s d4. Tal describes the openings well, as well as all other parts of the games, and it’s very instructive to read his notes and see how he’d decided which opening to employ depending on the match situation.

Game 1 - History Doesn’t Repeat Itself

Tal writes before game 1 that a loss in the first round wouldn’t surprise him. He had lost round 1 in the 1959 Candidates, in Zürich 1959, at the last Spartakiad before the match, and in the last USSR Championship! He writes: “This had gotten into my flesh and blood to such a degree that the score of the first game would come as no surprise to me, to my opponent, or to my chess friends, who would not begin to look for chess releases or buy the bulletins until the second round.”

I bet you remember game 1 from Ding – Gukesh in 2024, where Ding crushed Gukesh with the French. In 1960 it was the opposite. Tal defeated Botvinnik in the Winawer!

When you lose the first game of a match, you have to win to equalize! That sort of pressure increases with each draw. Tal writes: “We were very interested in how Botvinnik would try to even the score: would he go in for complications as in the first game or prefer slow, positional “squeezing! Tactics, keeping a sure draw in hand?”

It turns out that Tal never gave him a choice! His strategy was to keep pressing, keep inviting Botvinnik into tactical complications, and to keep searching for positions that suited the younger Mikhail better. Round 2 was a Benoni, round 3 a Caro-Kann where Tal played his famous 5.gxf3! Both games saw Tal risk more and fight for a win harder. Despite that, both have, as well as rounds 4 and 5, ended in a draw.

Game 6 - Nf4! Tal Wins in the King’s Indian With a Brilliant Sacrifice

“If Tal sacrifices a piece, take it. If Petrosian sacrifices a piece, don’t take it.” – Botvinnik

A one point lead is a lot in a match. Two points is almost game over. Tal continued pressing in each game, and, despite often fighting for a draw out of a worse position, he didn’t change strategies. He triumphed in game 6, where he unleashed a sacrifice everyone is familiar with today – Nf4!! 2-0 for Tal.

Game 7 - Is the Match Already Over?

After game 6 Tal writes: “My mood after the sixth game was understandably significantly improved. I had not only won a second point but I had finally gotten a position that was to my taste.” Tal was cooking up a knight sac from round 5, and, having noticed the possibility, Botvinnik had avoided the same variation in game 7. The deviation, as it turned out in game 9, where Tal did play 11.Nxe6 finally, wasn’t a good idea.

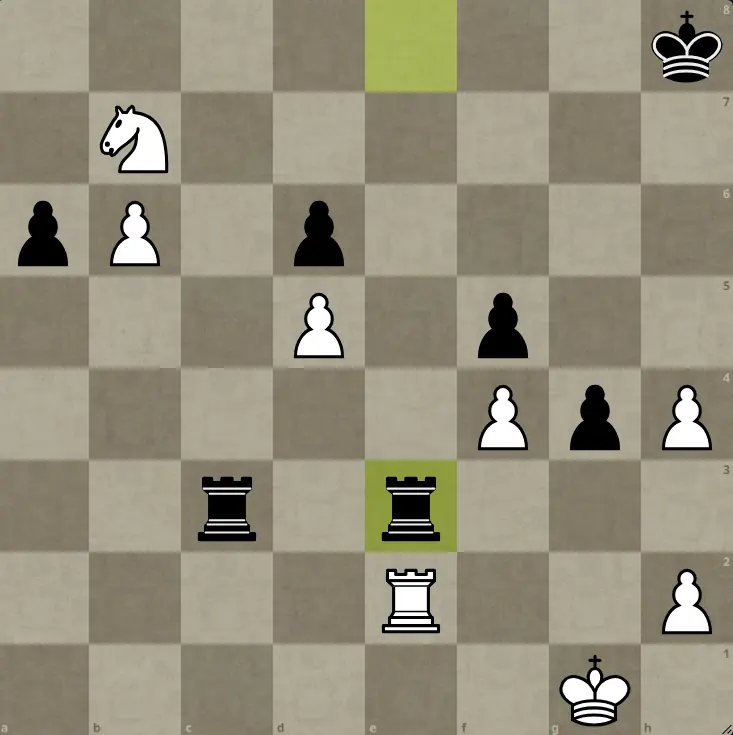

Tal played very precisely and Botvinnik too, almost perfectly. Until the pressure started increasing. Tal’s rooks and bishop eventually forced Botvinnik into a rook for two knights imbalance, which was easily convertible for Tal. 3-0 for Tal. You don’t come back from that if you’re Botvinnik. Or do you?

Games 8 and 9 - Botvinnik Strikes Back!

What Botvinnik did next is remarkable. Staying focused and fighting on despite being in an almost hopeless situation is worthy of praise and proves that Botvinnik is considered to be one of the greatest champions of the 20th century for a reason. Well. Tal may have helped him just a bit.

Having a 3-0 lead, Tal employed a bad match strategy. He writes: “From a sporting point of view, it might have been very clever to begin to stress quiet play after the 7th game, assuming my opponent would throw himself into risky attacks… But to play for a draw in 17 games was a very unpleasant prospect. If one considers I was not yet in top form, then our decision will be understood: to attempt to intensify the tactical struggle.” Tal was a boss. This one sentence proves it. Imagine being up 3 points and, instead of being content with quiet chess, you actively seek further complications and wilder games in the rest of the match!

His strategy immediately backfired. He played a Modern Benoni – the son of sorrow, the sharpest opening against d4. His position was ok, and it should have ended in a draw, albeit a sharp one, but then came move 38. 3-1 for Tal.

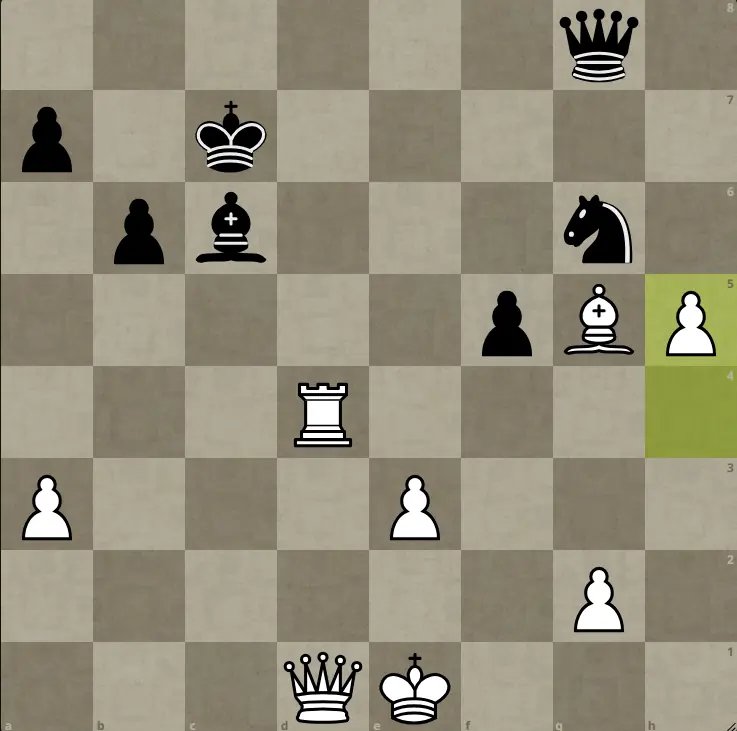

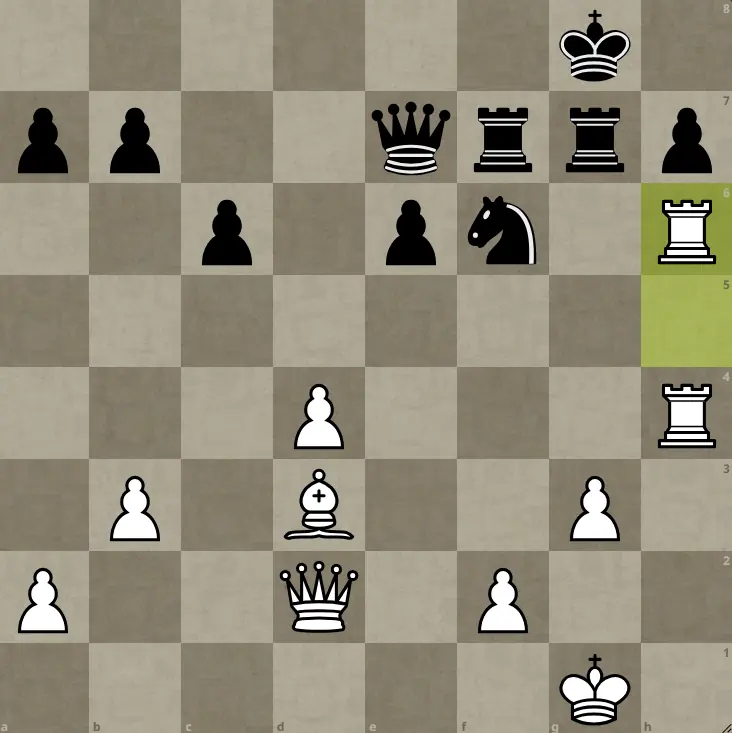

Here’s a famous position from game 9, in which Tal had unleashed his prepared sacrifice 11.Nxe6, something he’d been considering in game 5 for almost 40 minutes. Botvinnik was defending tenaciously. How would you evaluate it?

The Match Has Only Just Begun

After 9 games the score was 3-2 for Tal. The seemingly insurmountable lead melted away, and Botvinnik had the upper hand psychologically. Game 10 ended in a draw.

Game 11 - Tal Doesn’t Play e4?

Before game 11, Tal and Koblents, his coach, had decided that they’d had enough of trying to break Botvinnik’s Caro-Kann, and Tal ended up playing 1.Nf3. It was a Reti against a Grunfeld setup. Tal mounted a strong kingside attack that ended up transposing to a winning queen endgame he had no trouble converting.

A Matter of (Match) Endgame Technique

After round 11, Botvinnik was unable to catch up. Tal was up 2 points. He managed to secure draws in rounds 12-16, with numerous chances for both players, and then sealed the match in game 17. The rest of the match, the final four games, were a formality. In game 21, where Botvinnik still had a mathematical chance to come back, but had needed four consecutive wins, he had offered a draw on move 17 and the match was over. The Magician from Riga became the World Champion!

His reign was short-lived. In 1961, during their rematch, Botvinnik destroyed Tal 13-8, an even more convincing result than Tal’s 12.5-8.5 in the first match.

Other Chess Books on World Championship matches you might like:

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- The world Chess Crown Challenge: Kasparov vs Karpov, Seville 87

- David Bronstein

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- Botvinnik – Petrosian: 1963 World Chess Championship Match

- Mihail Botvinnik

Quality of Tal’s Annotations

The true value of Tal-Botvinnik 1960 are Tal’s annotations. I read many editions of the book, but the one I’m reviewing is the 2016 edition by Russell, which includes move times and all of Tal’s original comments.

Imagine a chess book that has a paragraph written for each move – that’s Tal-Botvinnik. Tal explains everything in a way a child could understand despite being the strongest player in the world at the time.

His annotations are relevant today, as not many crucial mistakes occurred in his analysis. Even his comments on the openings during the match are almost as instructive today, since it was exactly him who had contributed much to the attacking ideas in the Benoni and the KID, and Botvinnik who had helped develop the theory and strategy in the Caro-Kann we still employ today.

Tal references numerous games played before the match to compare positions and variations. That is incredibly helpful. More so because he played the tournaments where those games were played and he knew them inside-out. His sublime knowledge is obvious on every page.

Conclusion

Tal-Botvinnik 1960 is the best chess book on a match or a tournament in history. Annotated by Tal himself, it includes detailed descriptions of all 21 games played, as well as his thoughts before the games, his preparation and strategy. That is something no one has done remotely so well before or since the first edition was published. This is my favorite chess book and I’ve read it many times, so I’m biased. I also play and love the Caro-Kann, Botvinnik’s main weapon, and I fear and avoid the positions Tal had chosen during the match, so the book is very relevant to me personally. Despite that, the instructive and historical value of Tal-Botvinnik is very objective. Read this book. You will love it and learn from it. You also won’t be able to take part in educated chess conversations until you do.

Other Game Collections you might like:

- ELO: 1600

- -

- 1800

- From Vienna to Munich to Stockholm: A Chess Biography of Rudolf Spielmann

- Grigory Bogdanovich